Old Man Afrika shouting at the world

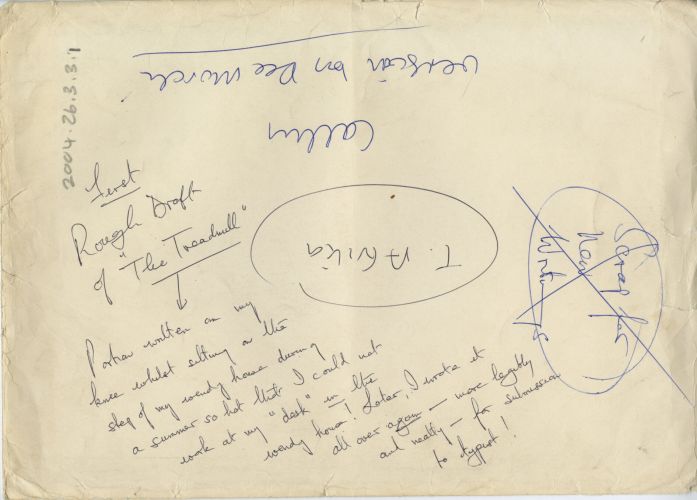

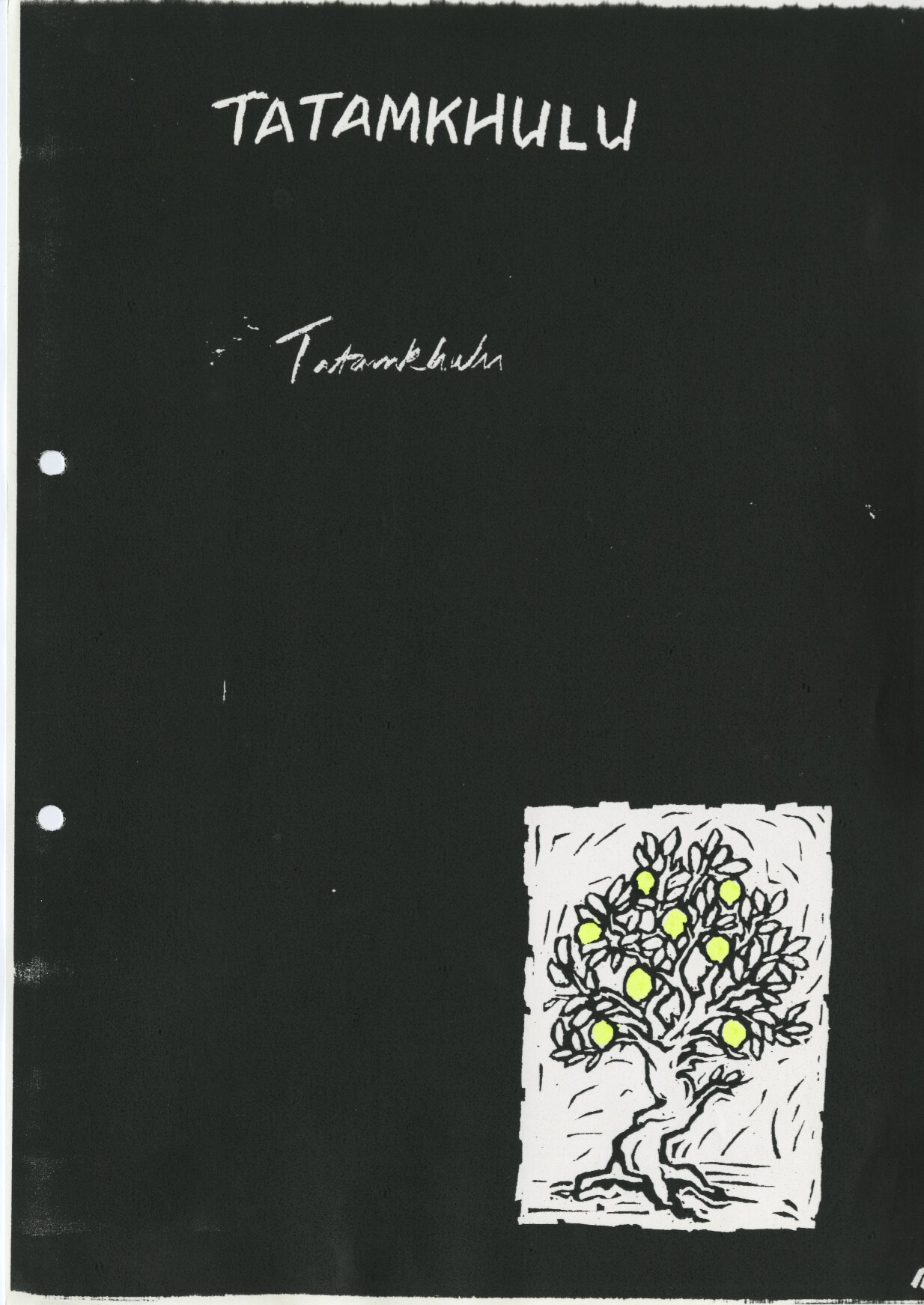

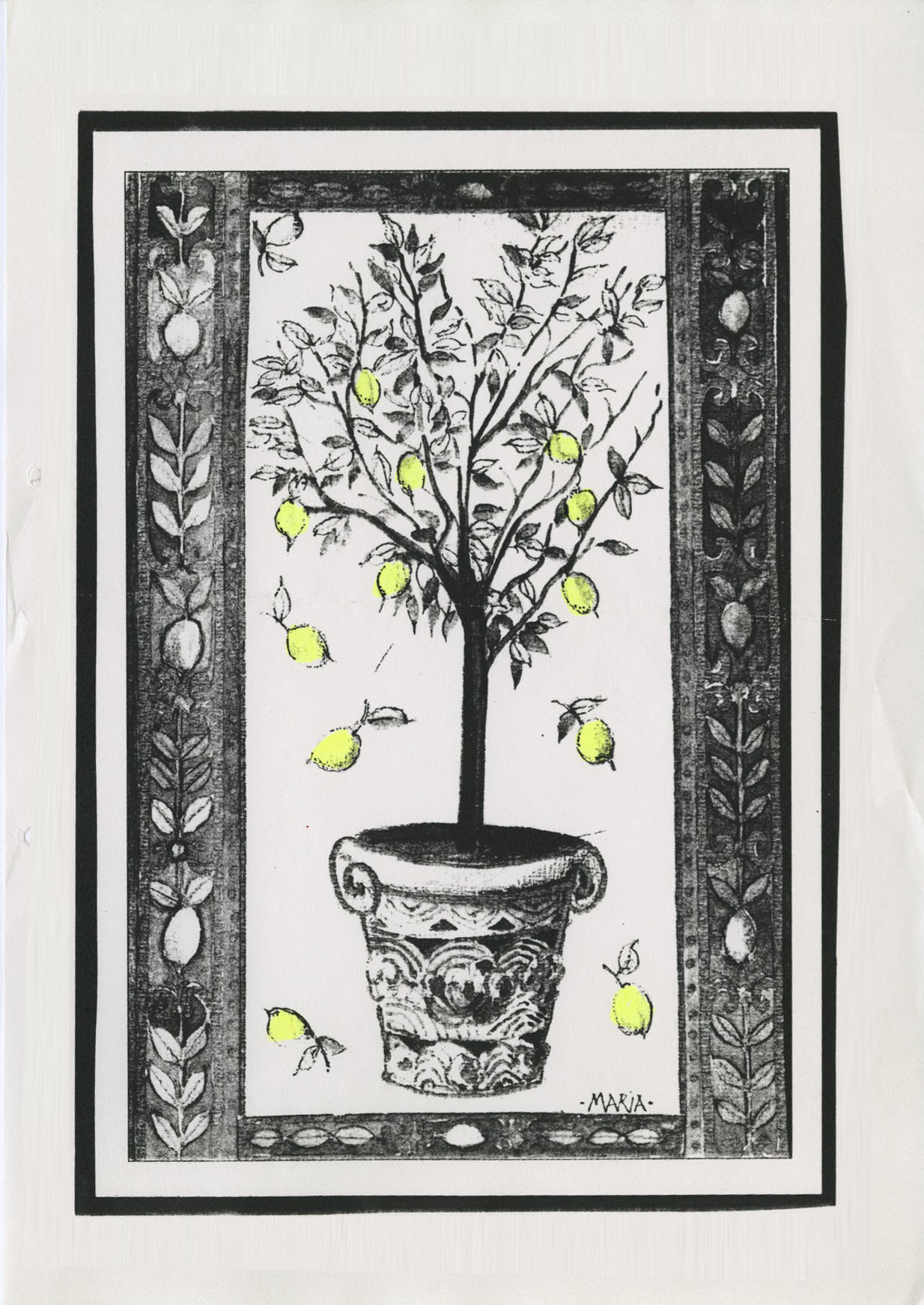

Artwork by Mel Hagen for the cover of Tatamkhulu Afrika’s Dark Rider (1992).

It is inscribed by the artist: “To Tatamkulu Afrika, A great poet and a true patriot, Mel Hagen 1992”.

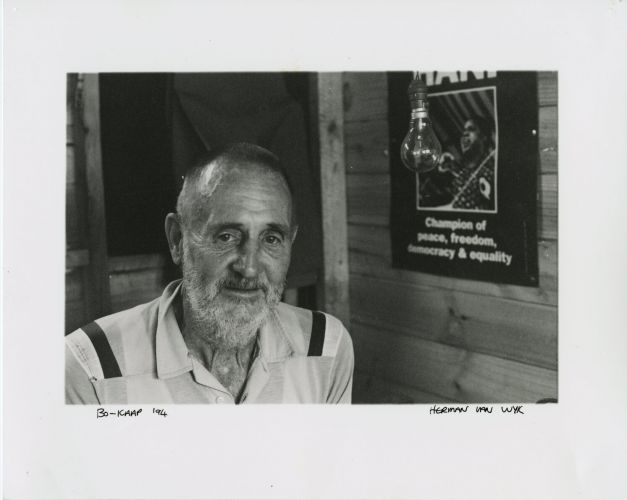

Tatamkhulu Afrika

But I have. I do. In every poem, every novel. That’s all my autobiography.From a conversation with Robin Malan, 2000.

The man who became Tatamkhulu Afrika wrote his first novel, Broken Earth, as John Charlton at the age of 17.It was published in 1940 by Hutchinson in London. More than 50 years would elapse before the publication of his next work, the poetry collection Nine Lives.

Afrika wrote about the everyday experiences of the poor and the dispossessed. He also wrote what he called the story of “a warts-and-all-man” – the autobiographical Mr Chameleon, published posthumously in 2005. This is characterised by ruthless and honest self-reflection and presents not only his achievements, but also his vulnerabilities. Mzi Mahola paid tribute to this openness: “He is like a person standing on top of a mountain, naked, shouting at the world to scrutinize and judge him”.

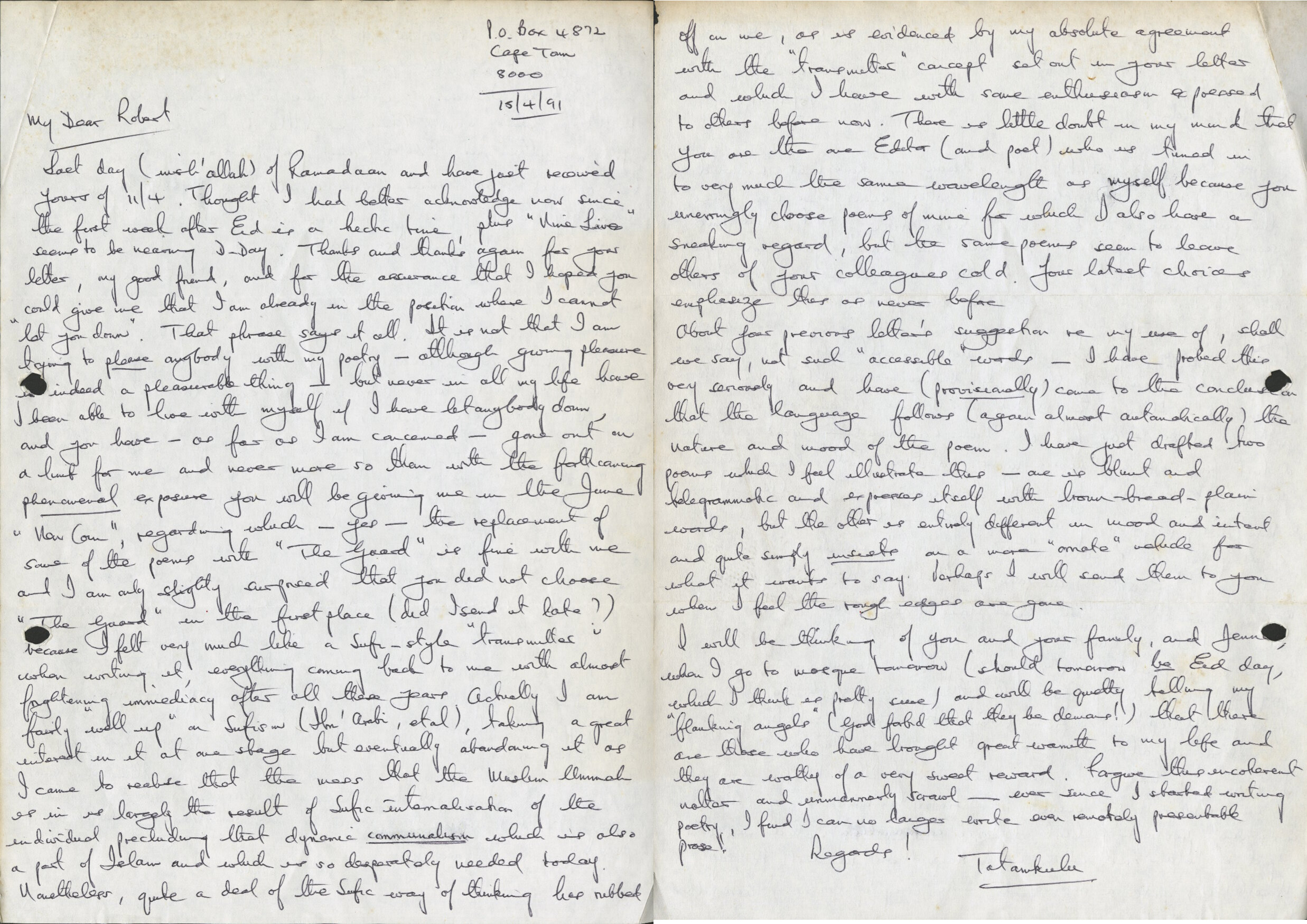

Interview by Marike Beyers with Robert Berold - an editor and friend of Afrika.

Tatamkhulu Afrika

But I have. I do. In every poem, every novel. That’s all my autobiography.From a conversation with Robin Malan, 2000.

The man who became Tatamkhulu Afrika wrote his first novel, Broken Earth, as John Charlton at the age of 17.It was published in 1940 by Hutchinson in London. More than 50 years would elapse before the publication of his next work, the poetry collection Nine Lives.

Afrika wrote about the everyday experiences of the poor and the dispossessed. He also wrote what he called the story of “a warts-and-all-man” – the autobiographical Mr Chameleon, published posthumously in 2005. This is characterised by ruthless and honest self-reflection and presents not only his achievements, but also his vulnerabilities. Mzi Mahola paid tribute to this openness: “He is like a person standing on top of a mountain, naked, shouting at the world to scrutinize and judge him”.

Interview by Marike Beyers with Robert Berold - an editor and friend of Afrika.

The five names of Tatamkhulu Afrika

I came down through the dead land,placing my feet well,

threading through its bones.

From ‘Quest’, 1994

Tatamkhulu Afrika lived up to the name ‘Mr Chameleon’. He was known by five different names over the course of his life, which reflects on his choices and identity in different periods.

Mogamed Fu’ad Nasif

He was born on 7 December 1920 in As-Sallum, close to Tobruk, Egypt, of an Egyptian father and a Turkish mother. The family came to South Africa in 1923.

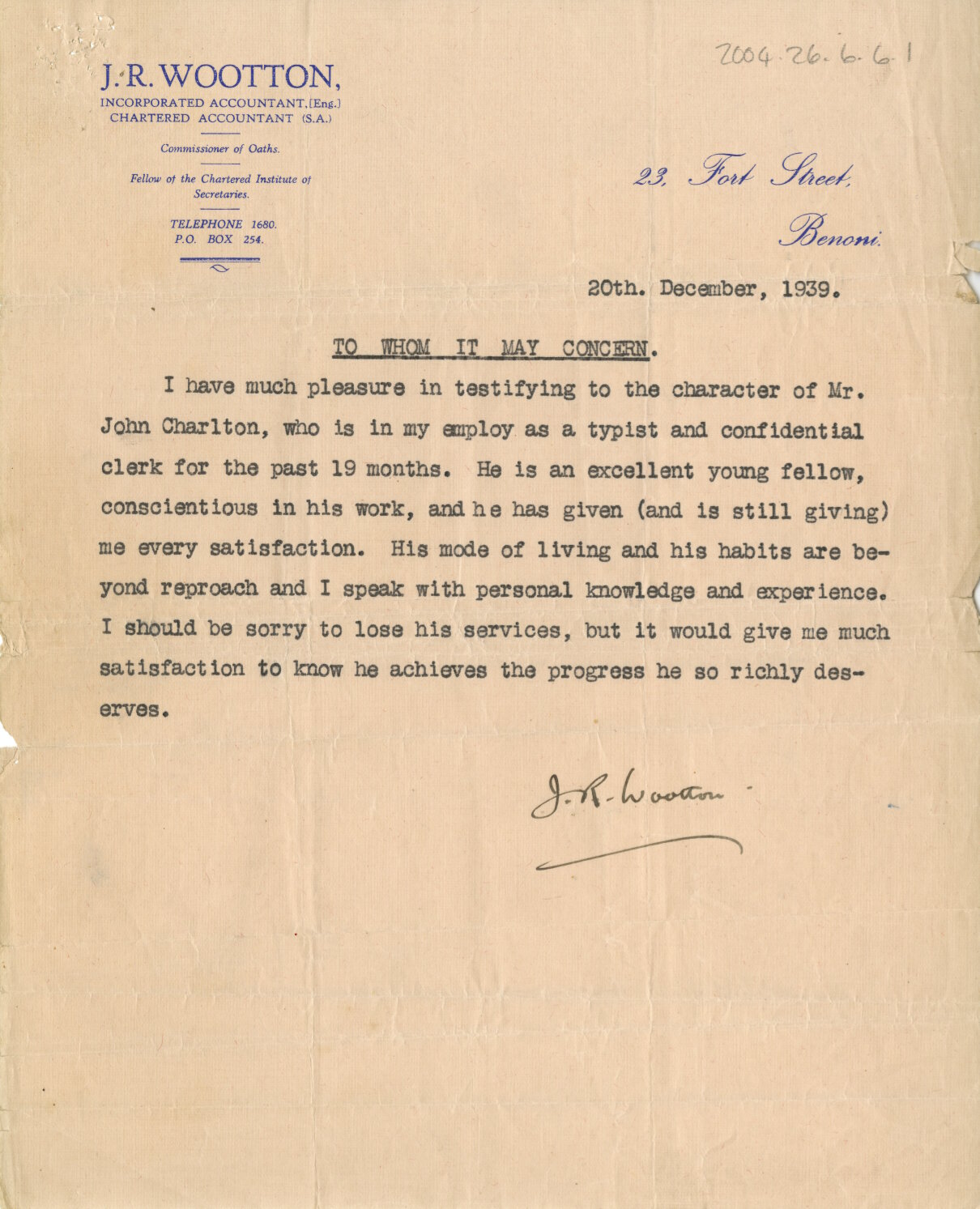

John Charles Charlton

The orphaned child was fostered by a white Methodist family who farmed in the Louis Trichardt district in the then Transvaal. He was given the name John Charles Charlton and went to school in Klerksdorp. The family lost the farm during the Great Depression of the 1930s and moved to the East Rand (Benoni). This was a time of emotional distress for Charlton and he left school before completing matric to write Broken Earth, a coming-of-age story against the background of city-farm imagery. He volunteered to serve in the Union Defence Force during World War II.

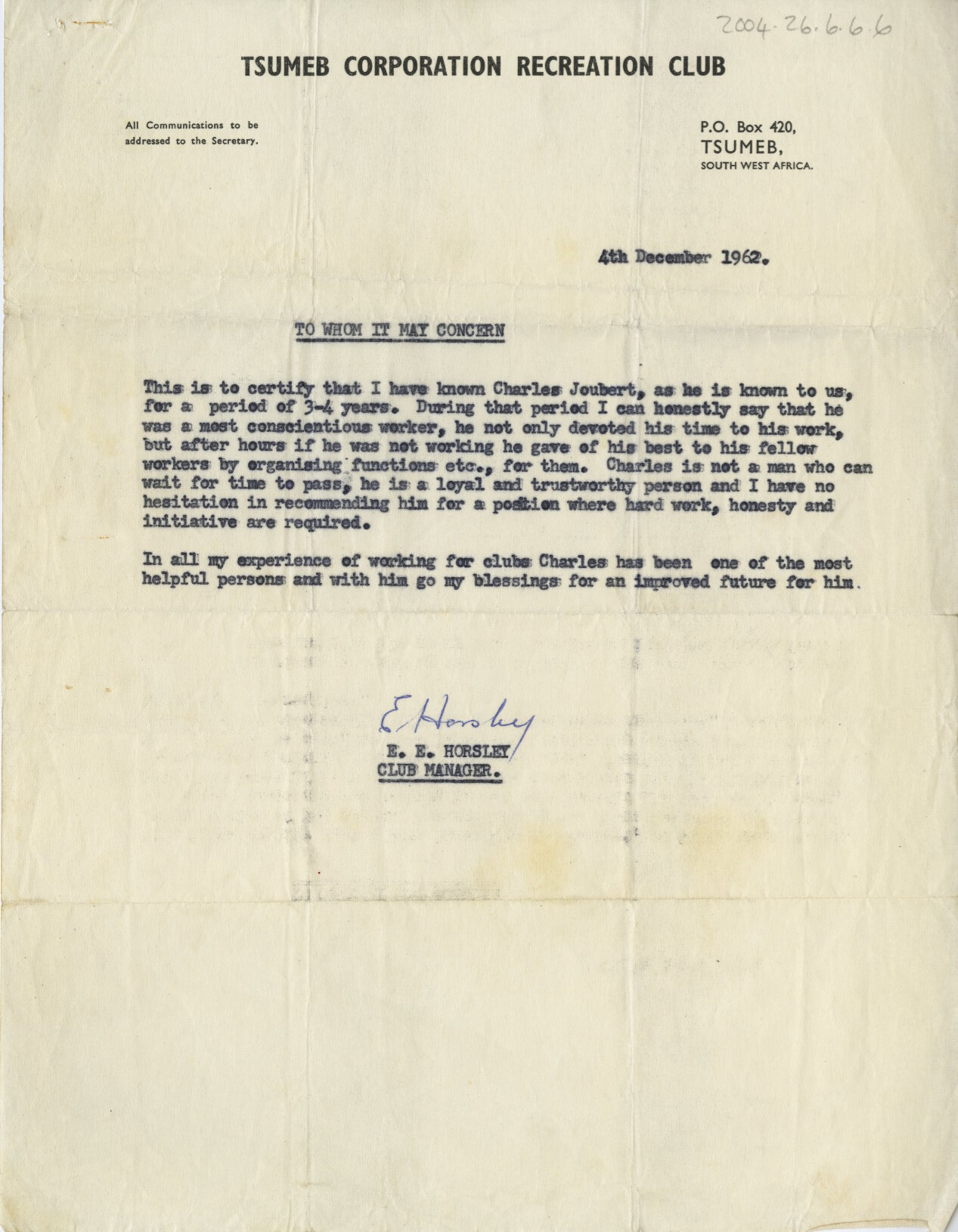

Jozua Francois Joubert

After World War II he lived in the Groot Marico for a few years and then in Tsumeb, South West Africa (now Namibia). In 1955 he changed his name in recognition of a family who supported him during this period. However, he was not known by this name but still called Charles or Charlie. In the early 1960s he moved to Cape Town and had himself reclassified as Malay, bearing the name Jozua Francois Joubert.

Ismail Joubert

In 1964 he converted to Islam and was given the name of Ismail. He lived in District Six and protested the forced removal of its inhabitants and its destruction under the Group Areas Act. He founded the organisation Al-Jihaad (worthy struggle or holy war), a welfare organisation with links, later, to uMkhonto weSizwe (MK).

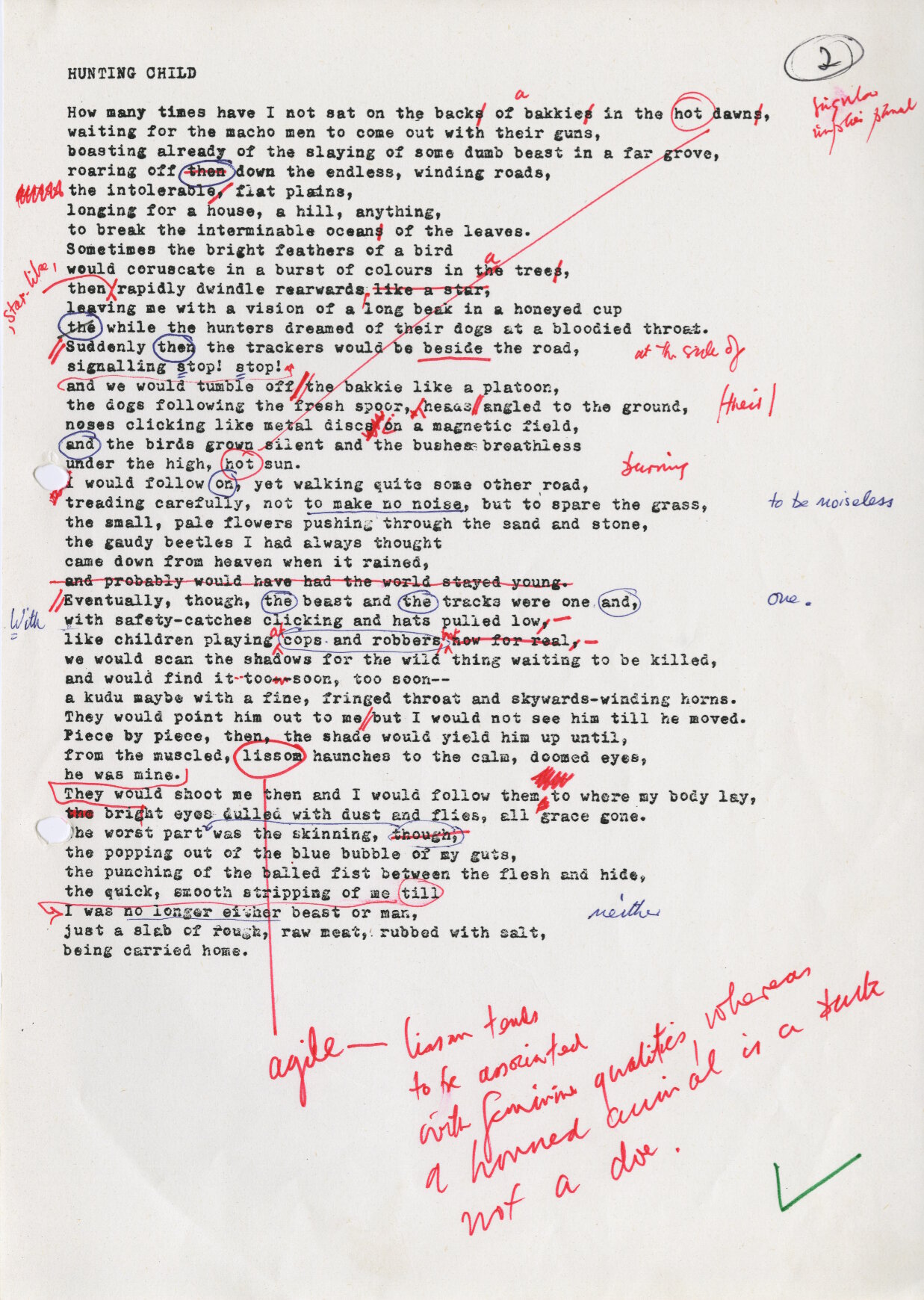

Tatamkhulu Ismail Afrika Tatamkhulu Afrika, which means Grandfather or Old Man Afrika, was a praise name bestowed on him by his MK comrades. Initially he used it as a pseudonym when he was banned from publication, but formally changed his name to Tatamkhulu Ismail Afrika in 1996. Afrika died on 23 December 2002 from injuries sustained in a road accident two weeks earlier.

The five names of Tatamkhulu Afrika

I came down through the dead land,placing my feet well,

threading through its bones.

From ‘Quest’, 1994

Tatamkhulu Afrika lived up to the name ‘Mr Chameleon’. He was known by five different names over the course of his life, which reflects on his choices and identity in different periods.

Mogamed Fu’ad Nasif

He was born on 7 December 1920 in As-Sallum, close to Tobruk, Egypt, of an Egyptian father and a Turkish mother. The family came to South Africa in 1923.

John Charles Charlton

The orphaned child was fostered by a white Methodist family who farmed in the Louis Trichardt district in the then Transvaal. He was given the name John Charles Charlton and went to school in Klerksdorp. The family lost the farm during the Great Depression of the 1930s and moved to the East Rand (Benoni). This was a time of emotional distress for Charlton and he left school before completing matric to write Broken Earth, a coming-of-age story against the background of city-farm imagery. He volunteered to serve in the Union Defence Force during World War II.

Jozua Francois Joubert

After World War II he lived in the Groot Marico for a few years and then in Tsumeb, South West Africa (now Namibia). In 1955 he changed his name in recognition of a family who supported him during this period. However, he was not known by this name but still called Charles or Charlie. In the early 1960s he moved to Cape Town and had himself reclassified as Malay, bearing the name Jozua Francois Joubert.

Ismail Joubert

In 1964 he converted to Islam and was given the name of Ismail. He lived in District Six and protested the forced removal of its inhabitants and its destruction under the Group Areas Act. He founded the organisation Al-Jihaad (worthy struggle or holy war), a welfare organisation with links, later, to uMkhonto weSizwe (MK).

Tatamkhulu Ismail Afrika Tatamkhulu Afrika, which means Grandfather or Old Man Afrika, was a praise name bestowed on him by his MK comrades. Initially he used it as a pseudonym when he was banned from publication, but formally changed his name to Tatamkhulu Ismail Afrika in 1996. Afrika died on 23 December 2002 from injuries sustained in a road accident two weeks earlier.

The young chameleon

His grandmother’s explanation for the chameleon changing colour: “It’s the way he gets what he wants, dear, and the way he hides from those who want him!”From Mr Chameleon, 2005

Afrika saw his younger self as mutable and refers to himself as Mr Chameleon in his autobiography. When writing about his childhood, difficult family relations are apparent. He acknowledges a bond with his mother and her family, but consistently refers to the father figure in his life as his stepfather. His mother only told him about his Egyptian origins when he was a teenager with the request to keep this information private as a defence against racial prejudice.

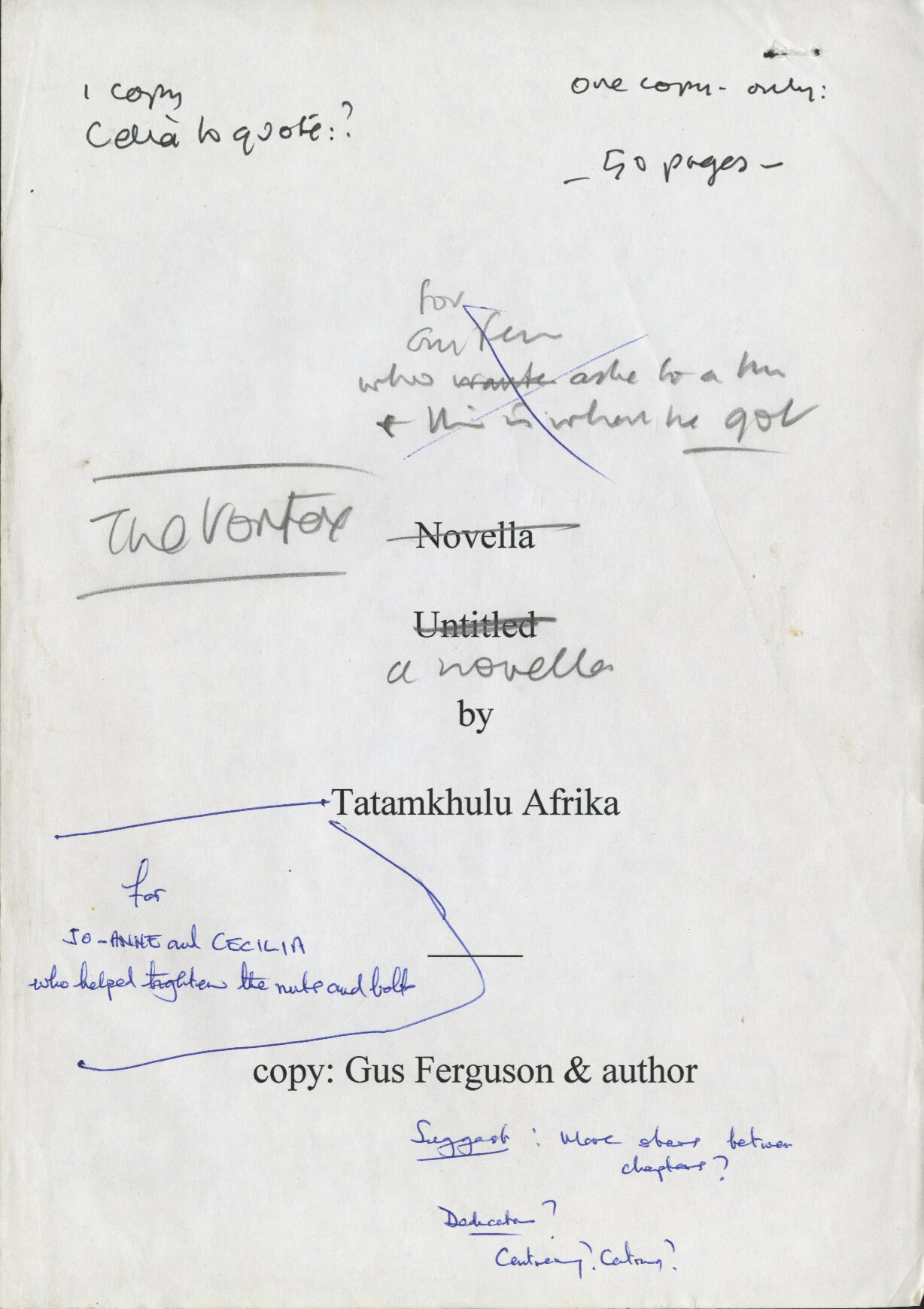

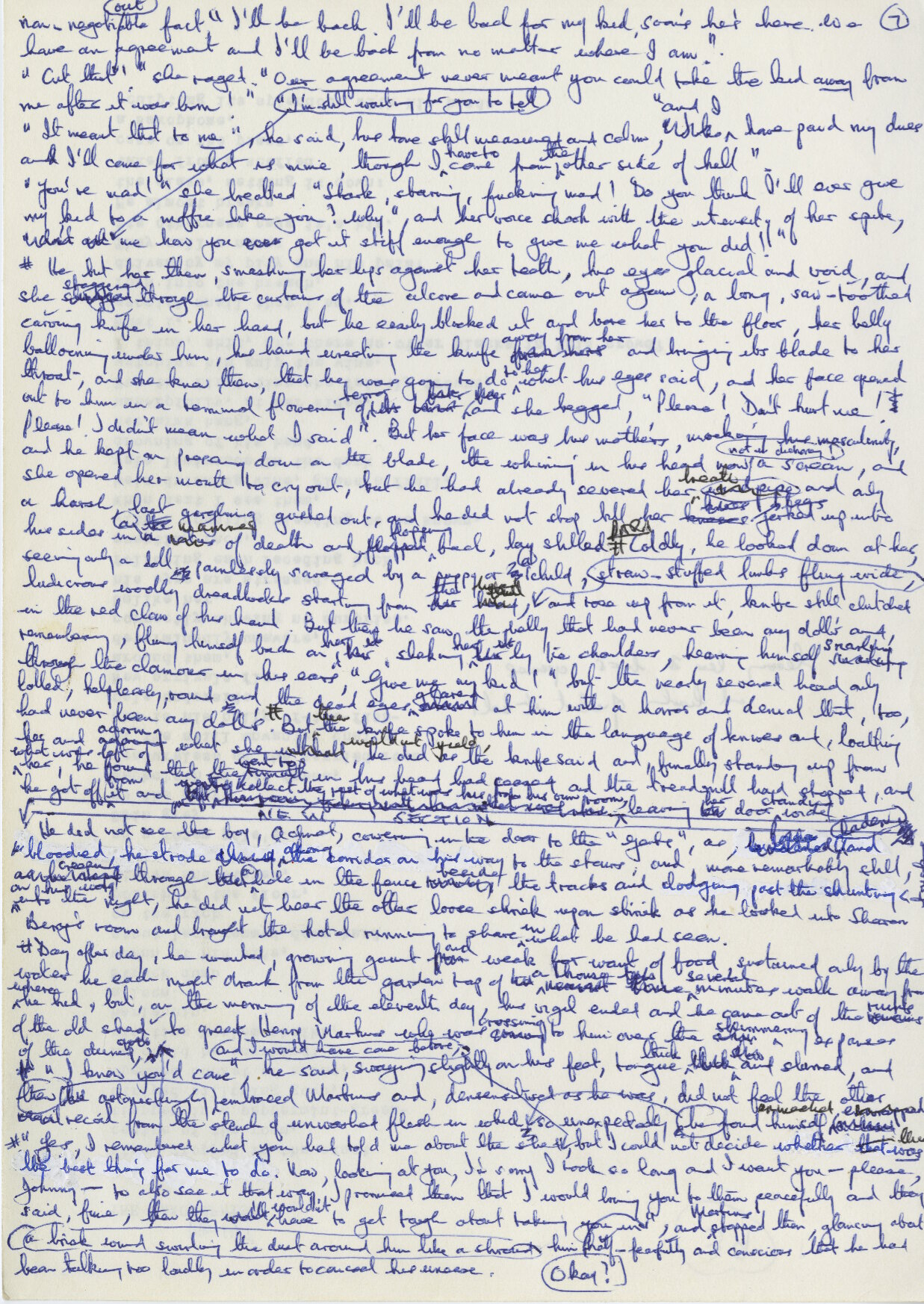

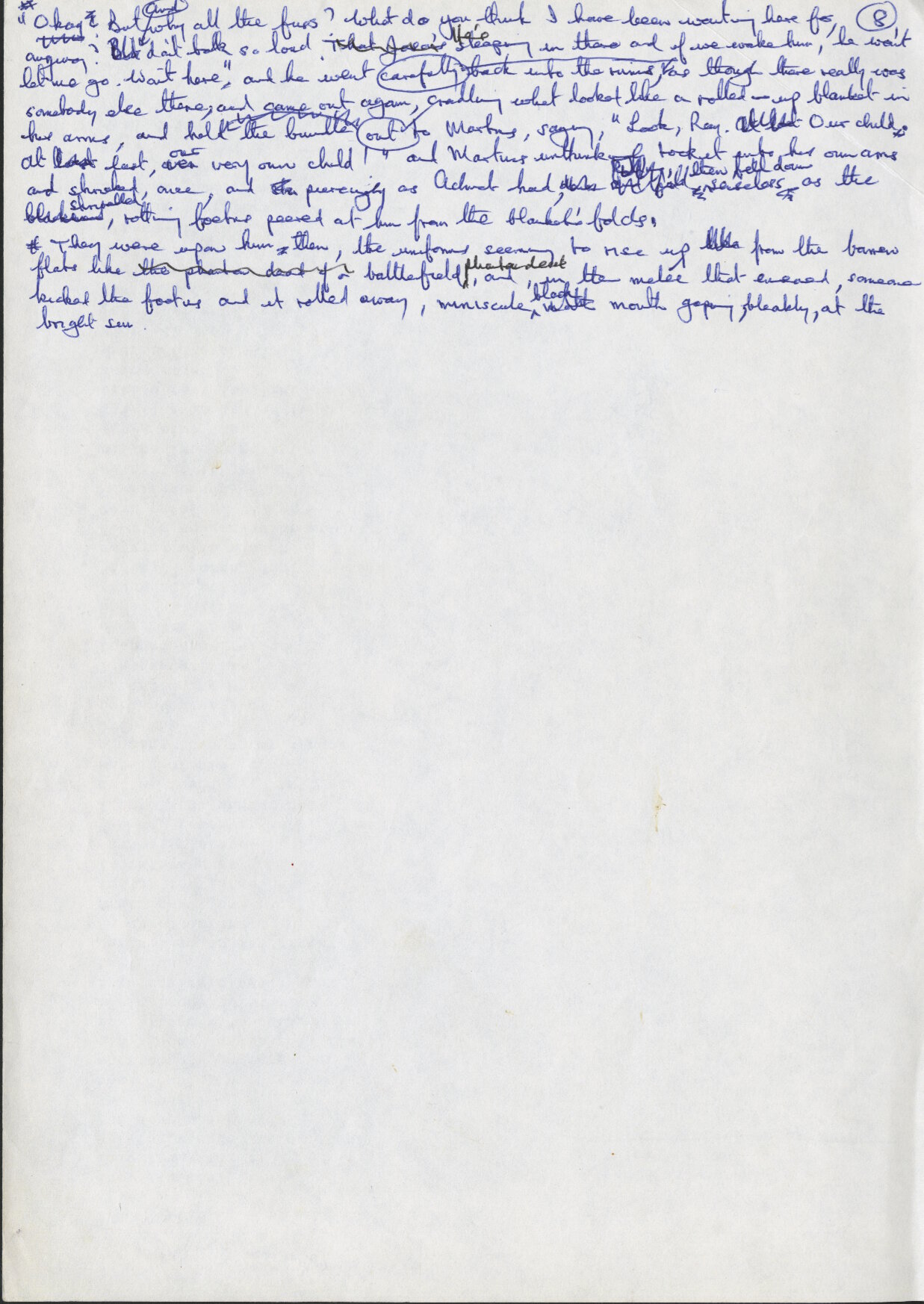

There are direct parallels between his autobiographical writing about his childhood and his fiction, particularly in the novellas ‘The Vortex’ and ‘The Treadmill’. This can be seen in several of the characters, such as the domineering, even abusive father figure, the young character Johnny – who leaves school early and is precocious but emotionally immature – and the character Ray – a cinema doorkeeper and a bit of a hustler – who is based on a young man from the writer’s youth spent in thrall to the movies. There is a strong sense of place in presenting a West Transvaal town of the time.

Broken Earth ,written at the age of 17, can be seen as a reversal of the ‘Jim-goes-to-Joburg’ theme then prevalent in South African fiction. A rather unlikable young character, John Wayne, is banished to work as a farm manager in the north of the country, where his foolish arrogance is satirised. The novel shows a nascent awareness of patriarchal social dynamics within and among different racial and cultural groups. The young author’s love for the country is apparent in detailed observations of the landscape and rural way of life and belonging to the land, and in a rather naïve vision of national unity.

The young chameleon

His grandmother’s explanation for the chameleon changing colour: “It’s the way he gets what he wants, dear, and the way he hides from those who want him!”From Mr Chameleon, 2005

Afrika saw his younger self as mutable and refers to himself as Mr Chameleon in his autobiography. When writing about his childhood, difficult family relations are apparent. He acknowledges a bond with his mother and her family, but consistently refers to the father figure in his life as his stepfather. His mother only told him about his Egyptian origins when he was a teenager with the request to keep this information private as a defence against racial prejudice.

There are direct parallels between his autobiographical writing about his childhood and his fiction, particularly in the novellas ‘The Vortex’ and ‘The Treadmill’. This can be seen in several of the characters, such as the domineering, even abusive father figure, the young character Johnny – who leaves school early and is precocious but emotionally immature – and the character Ray – a cinema doorkeeper and a bit of a hustler – who is based on a young man from the writer’s youth spent in thrall to the movies. There is a strong sense of place in presenting a West Transvaal town of the time.

Broken Earth ,written at the age of 17, can be seen as a reversal of the ‘Jim-goes-to-Joburg’ theme then prevalent in South African fiction. A rather unlikable young character, John Wayne, is banished to work as a farm manager in the north of the country, where his foolish arrogance is satirised. The novel shows a nascent awareness of patriarchal social dynamics within and among different racial and cultural groups. The young author’s love for the country is apparent in detailed observations of the landscape and rural way of life and belonging to the land, and in a rather naïve vision of national unity.

Prisoner of war

I would go out then,sky bright and bland,

silence heavy

as a pestilence in the land,

shrapnel crackling underfoot

like an iron frost, a manna cast

by devils for the damned.

From ‘Bombardment’, 1996

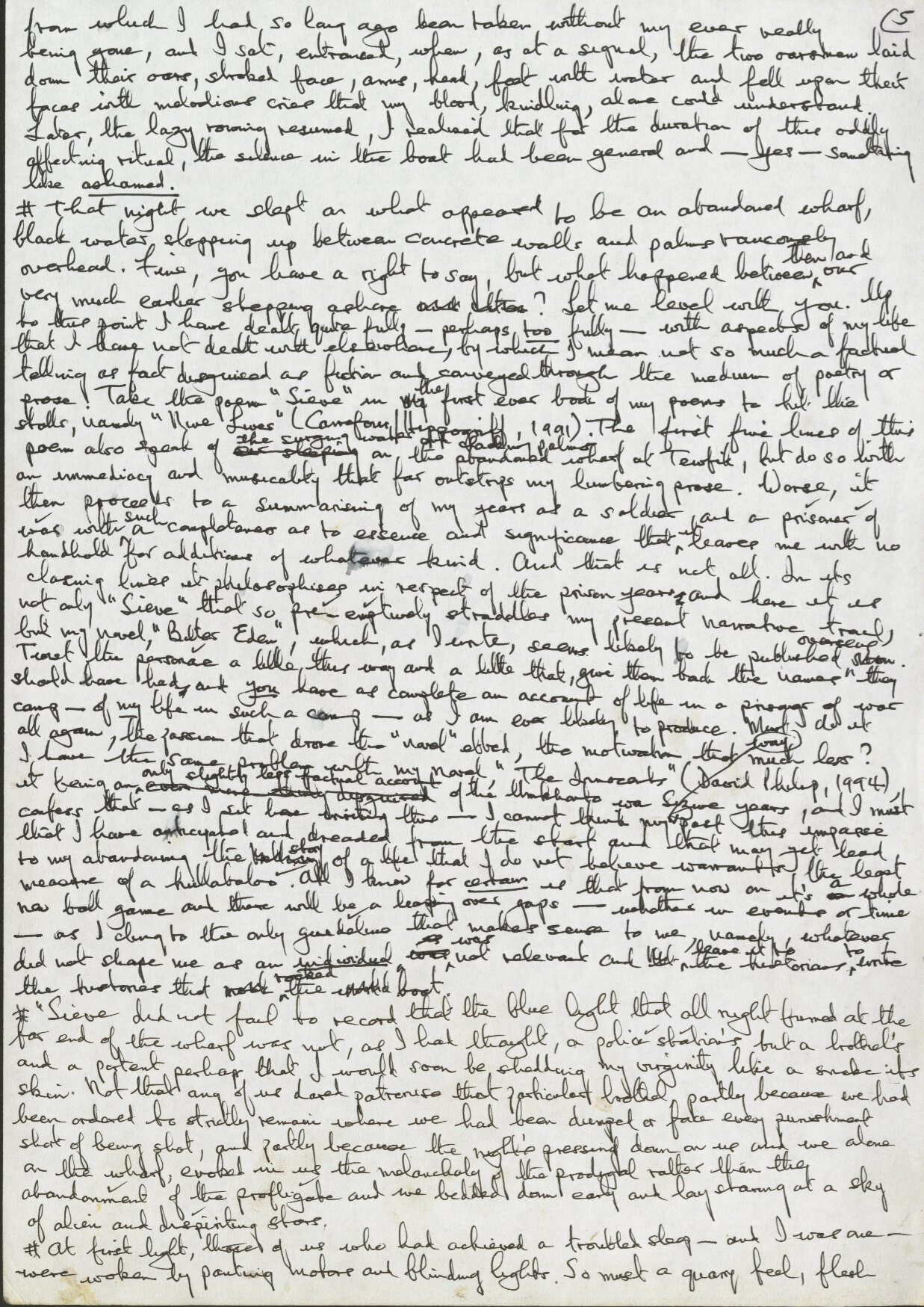

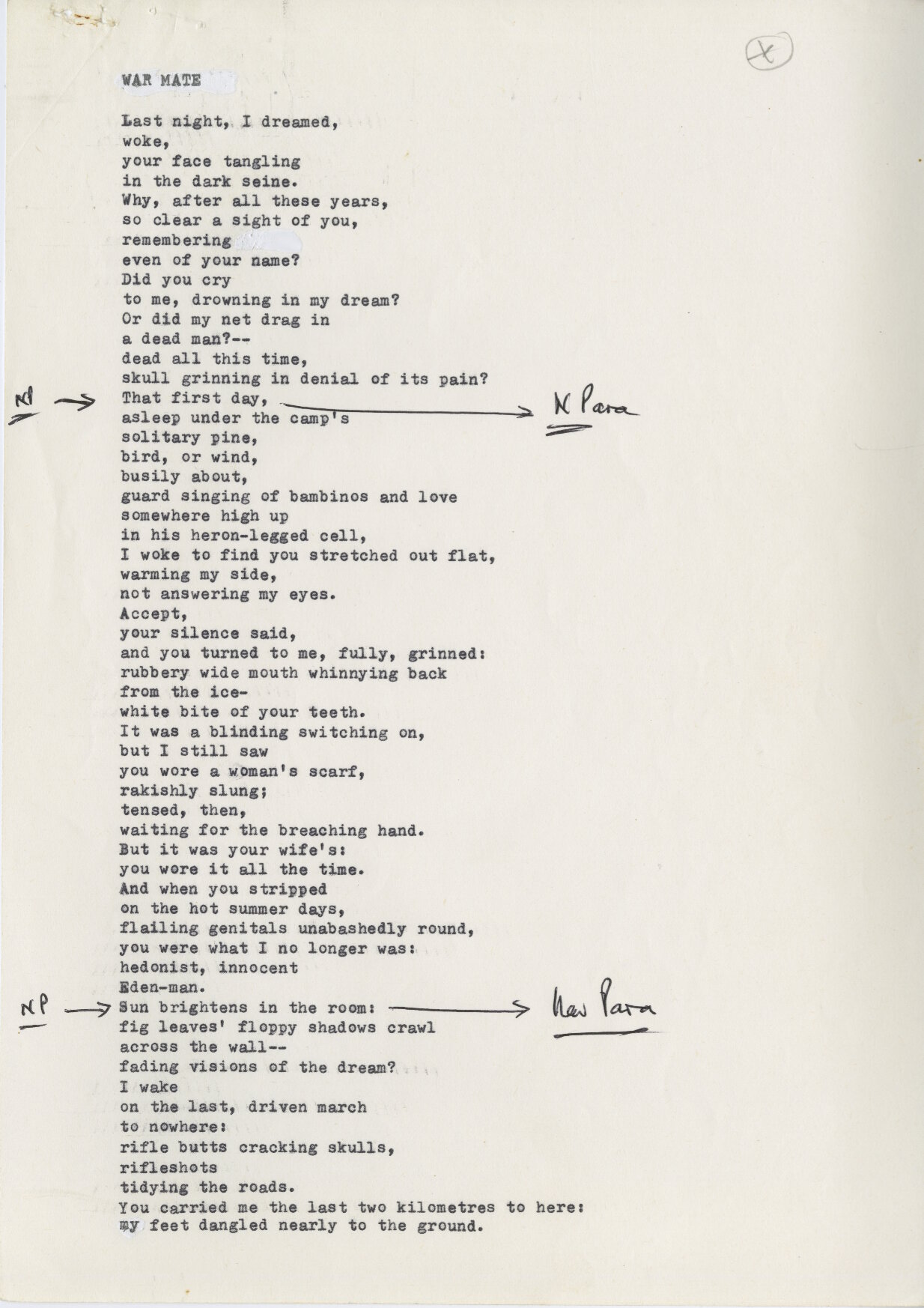

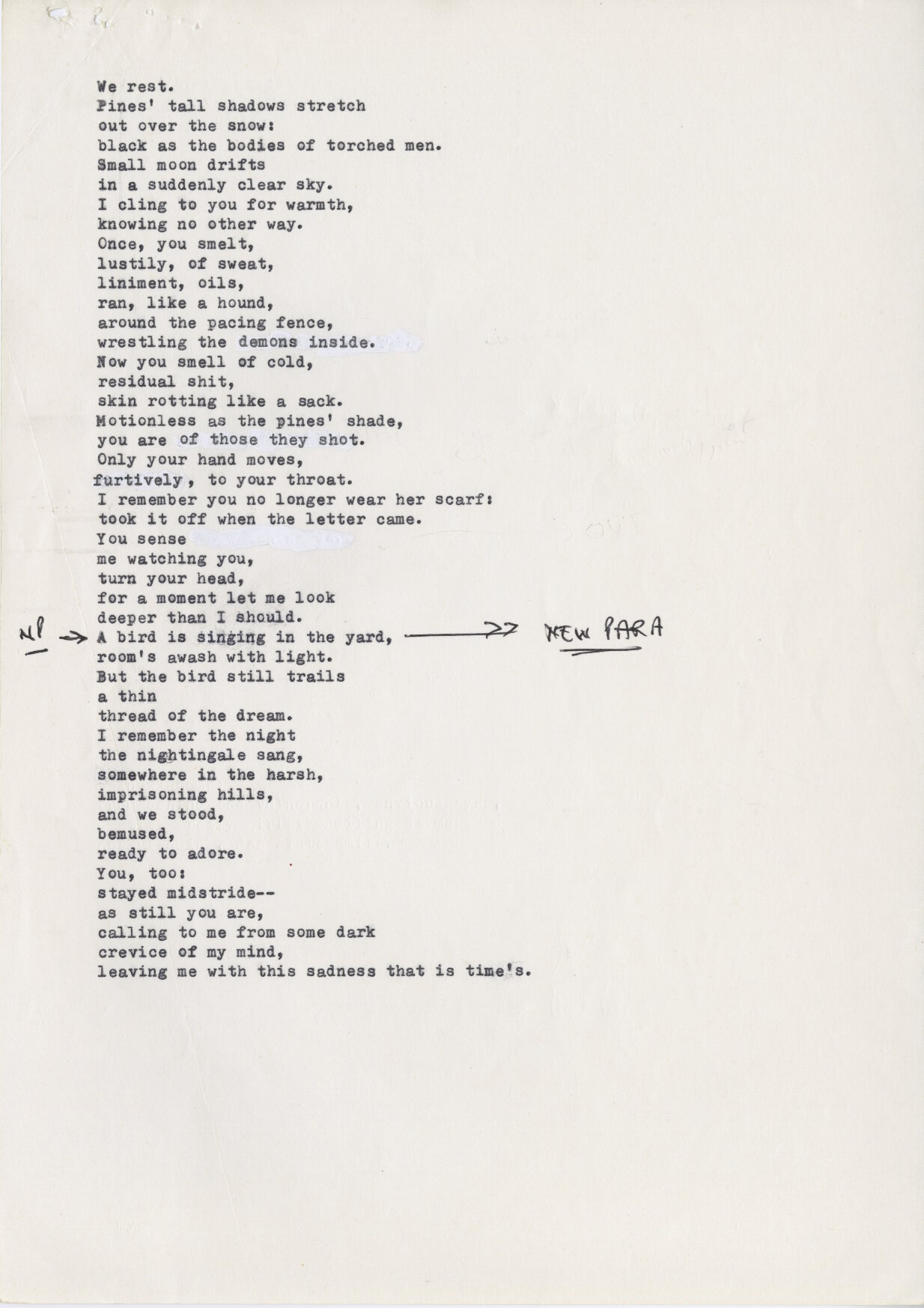

Afrika joined the Union Defence Force to escape his job as an accounting clerk and attended military college to train as an instructor before being sent to Egypt with the Second Infantry Division. He was captured at the fall of Tobruk in June 1942 and was a prisoner of war (POW), first of the Italians, mainly at Chiavari, and later of Nazi Germany at Lamsdorf. When the Nazis came under pressure towards the end of the war, the prisoners were sent on forced marches. Conditions were harsh and stragglers were shot. His life was saved by his close friend, Dennis, which is portrayed both in Afrika’s fiction and in the poem ‘War Mate’.

The author captured his life in a POW camp in his novel Bitter Eden, published in 2002. He describes the emotional tension of living in close proximity to others in conditions of deprivation and uncertainty, as well as day-to-day activities in the camp, especially plays staged by the prisoners. Afrika acted in Journey’s End by R.C. Sheriff and played Lady Macbeth in an adaptation of this Shakespeare drama. He also put on a performance of C. Louis Leipoldt’s Die Heks for the small audience who could understand Afrikaans. Staging plays and particularly presenting the roles of women characters feature in Bitter Eden as well. In the novel Afrika changed names and fictionalised aspects of his POW experience, particularly the demise of the character Douglas, to dramatise the love triangle between the narrator, Tom Smith, and his two friends, Douglas and Danny. The book is notable for the way it presents the topic of love between men who do not identify as homosexual.

Prisoner of war

I would go out then,sky bright and bland,

silence heavy

as a pestilence in the land,

shrapnel crackling underfoot

like an iron frost, a manna cast

by devils for the damned.

From ‘Bombardment’, 1996

Afrika joined the Union Defence Force to escape his job as an accounting clerk and attended military college to train as an instructor before being sent to Egypt with the Second Infantry Division. He was captured at the fall of Tobruk in June 1942 and was a prisoner of war (POW), first of the Italians, mainly at Chiavari, and later of Nazi Germany at Lamsdorf. When the Nazis came under pressure towards the end of the war, the prisoners were sent on forced marches. Conditions were harsh and stragglers were shot. His life was saved by his close friend, Dennis, which is portrayed both in Afrika’s fiction and in the poem ‘War Mate’.

The author captured his life in a POW camp in his novel Bitter Eden, published in 2002. He describes the emotional tension of living in close proximity to others in conditions of deprivation and uncertainty, as well as day-to-day activities in the camp, especially plays staged by the prisoners. Afrika acted in Journey’s End by R.C. Sheriff and played Lady Macbeth in an adaptation of this Shakespeare drama. He also put on a performance of C. Louis Leipoldt’s Die Heks for the small audience who could understand Afrikaans. Staging plays and particularly presenting the roles of women characters feature in Bitter Eden as well. In the novel Afrika changed names and fictionalised aspects of his POW experience, particularly the demise of the character Douglas, to dramatise the love triangle between the narrator, Tom Smith, and his two friends, Douglas and Danny. The book is notable for the way it presents the topic of love between men who do not identify as homosexual.

Dry places: From Groot Marico to Tsumeb

Like them [my characters], I have teetered between choices, moralities, sexualities, identities. Each novella foliates from a seed… of a personal experience; attains, then, a climax that never happened, but could have had the dice rolled otherwise.On writing Tightrope, 1996.

In the two decades following his return from World War II in 1945, Afrika worked as a barman, band manager and in various positions in the mining industry. He burnt his bridges in business and personal relationships in the Groot Marico area, so left for Tsumeb, South West Africa (now Namibia), in 1950 with the promise of work on the mines. He returned to South Africa for a brief spell when his mother became ill, but went back to Tsumeb after her death.

Afrika shows resilience and the ability to innovate and adapt. However, the novellas collected in Tightrope seem to echo an emotional desperation and barrenness in his life during this time. This is the bleakest of Afrika’s works. It is preoccupied with the testing of masculinity. Not a single relationship that might have afforded friendship or love survives the self-destructive tendencies of the characters or the complex legacies of their pasts. Examples of overlap with the autobiography include destructive bonds of male friendship in ‘The Vortex’, scenes of debauchery to which a strange sense of innocence clings in ‘The Treadmill’, the shame-filled death of a cat and a bird in ‘The Trap’, and the Buddy Da Silva character, who is an arrogant wannabe rock star running from racial prejudice in ‘The Quarry’.

Dry places: From Groot Marico to Tsumeb

Like them [my characters], I have teetered between choices, moralities, sexualities, identities. Each novella foliates from a seed… of a personal experience; attains, then, a climax that never happened, but could have had the dice rolled otherwise.On writing Tightrope, 1996.

In the two decades following his return from World War II in 1945, Afrika worked as a barman, band manager and in various positions in the mining industry. He burnt his bridges in business and personal relationships in the Groot Marico area, so left for Tsumeb, South West Africa (now Namibia), in 1950 with the promise of work on the mines. He returned to South Africa for a brief spell when his mother became ill, but went back to Tsumeb after her death.

Afrika shows resilience and the ability to innovate and adapt. However, the novellas collected in Tightrope seem to echo an emotional desperation and barrenness in his life during this time. This is the bleakest of Afrika’s works. It is preoccupied with the testing of masculinity. Not a single relationship that might have afforded friendship or love survives the self-destructive tendencies of the characters or the complex legacies of their pasts. Examples of overlap with the autobiography include destructive bonds of male friendship in ‘The Vortex’, scenes of debauchery to which a strange sense of innocence clings in ‘The Treadmill’, the shame-filled death of a cat and a bird in ‘The Trap’, and the Buddy Da Silva character, who is an arrogant wannabe rock star running from racial prejudice in ‘The Quarry’.

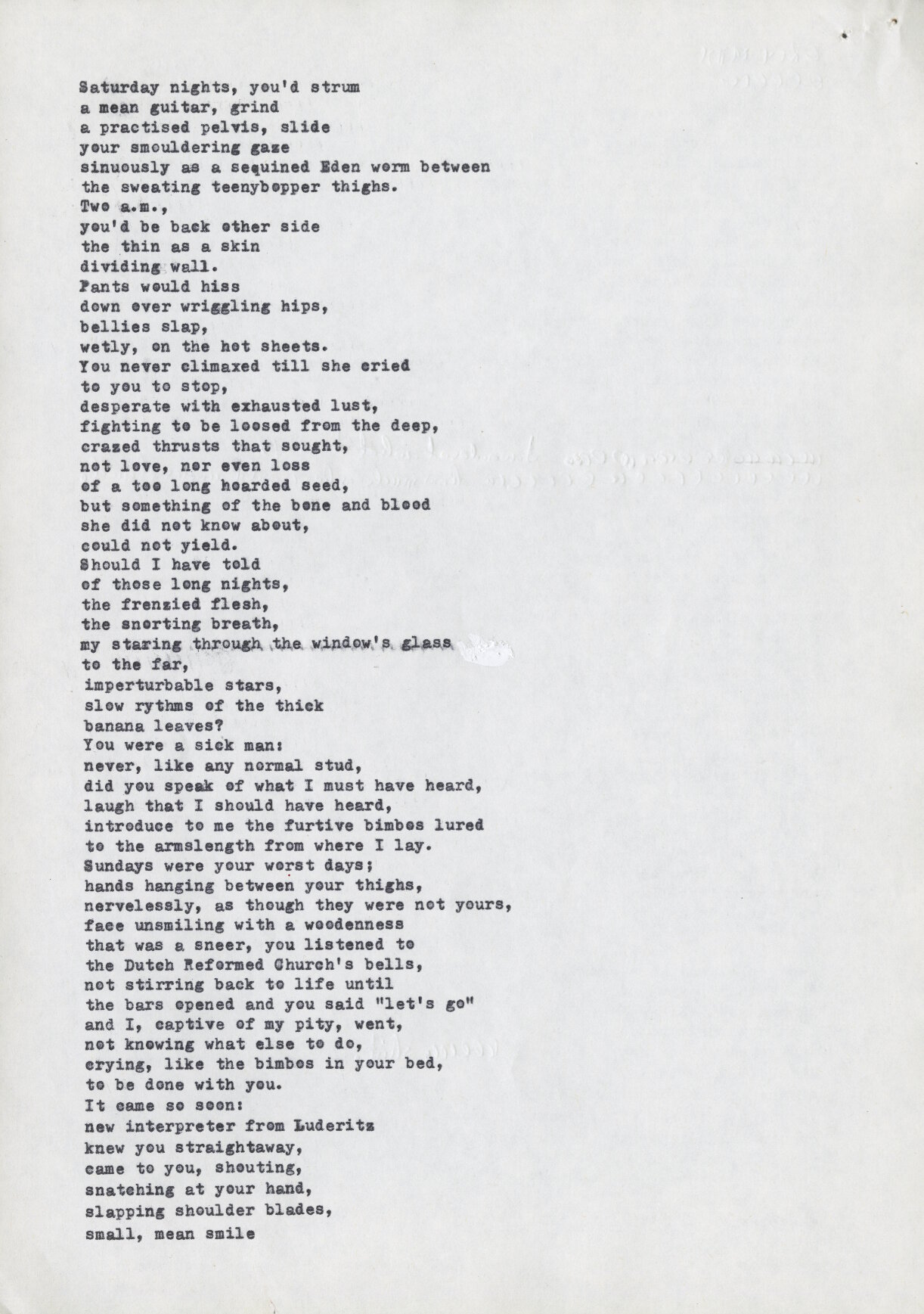

Bonds between men

… the question of male bonding… is one on which I hold particularly decided views. … I do not think that male bonding is the rugged, virginal affection between males that many books and the cinema screens would have us believe. In fact, the relationship is as lushly suggestive of intercourse… as a serious whore’s bed and is… a barely covert celebration of masculinity and a sharing, as barely restrained, of a hunger to once again run in packs and, together, rape and rend. Or did you really think that gay rape was a phenomenon of this day and age alone? And an adolescent, swinging between his Yin and his Yang … would such a bonding benefit or harm him?From Mr Chameleon, 2005

From early adulthood Afrika moved in male-dominated environments. In the 1940s he was a young soldier and prisoner of war and in the 1980s a political prisoner. He worked in small, outlying farming and mining towns with predominantly male companionship. Male hierarchies were also foremost in the public, active life he chose as a Muslim and anti-apartheid activist from the mid-1960s onwards.

In his life, and much of his writing, Afrika is intensely focused on matters of sexual identity and belonging. His intimate emotional connections are with men and the author moves between homoerotic and homophobic preoccupations. This conflict is never resolved. Even in Bitter Eden, where he fictionalises the dilemma of same-sex attraction, he cannot find middle-ground between an acceptable desire and taboo behaviour.

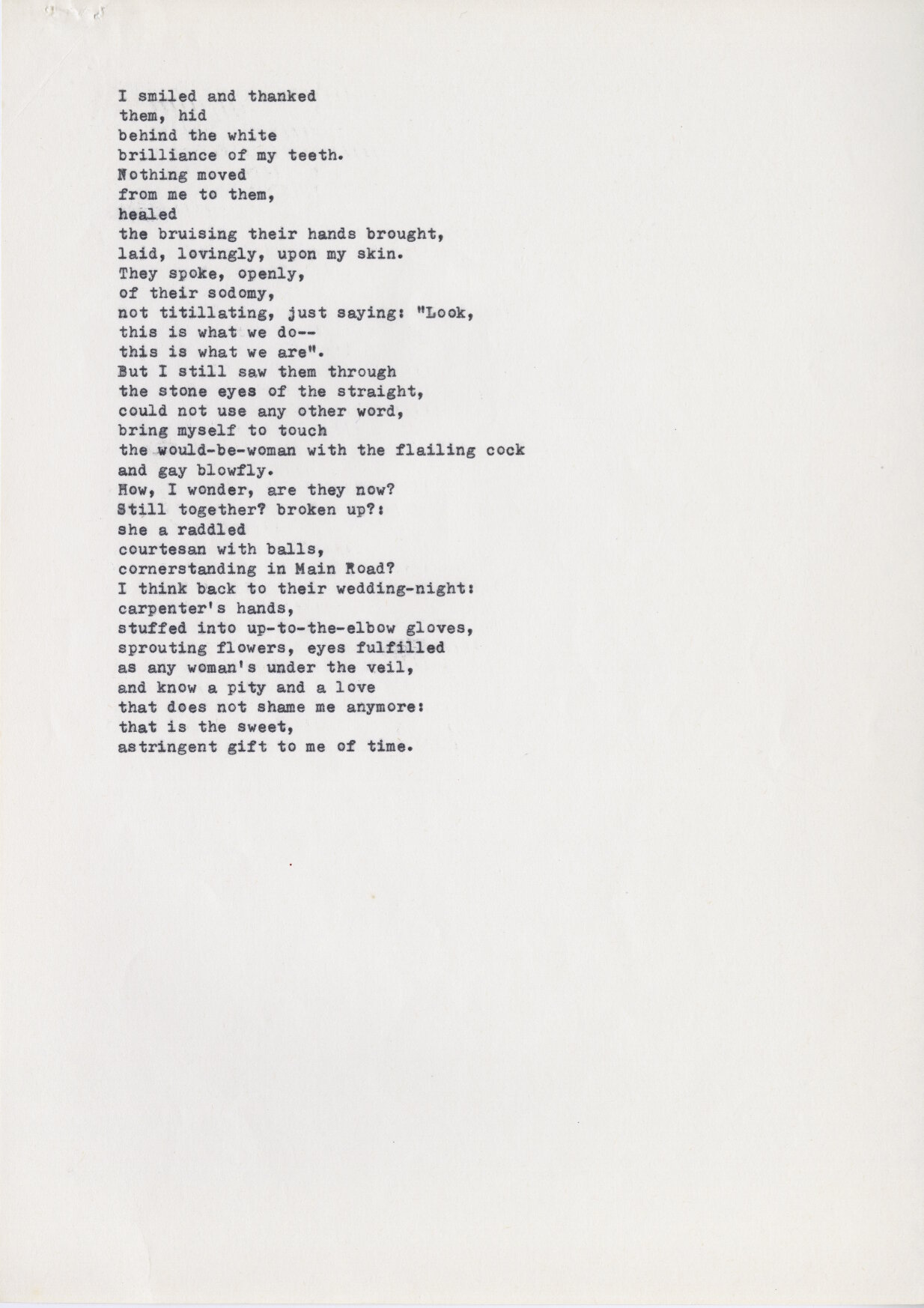

Although Afrika recoils from overt male desire, he demonstrates a fascination with the gay community in Cape Town. In the poem ‘Gay Samaritans’ he portrays a flamboyant couple who befriended him. In his work there is a sense of strong identification with the warmth he sees in meetings between men and a sense of wonder at men who feel easy in their nakedness.

The poem ‘The Groping’ presents a scene of sexual harassment, but it is also an example of his tendency to describe what is unwanted and ugly as feminine. Afrika’s conflicted nature also comes to the fore in the poems ‘Grey Man’ and ‘The Seeding’ where there is a movement between revulsion and tenderness, while ‘War Mate’ presents male bonding in heroic terms.

Afrika is willing to reveal his conflicted being. The tension between a desire to bond with other males and an often shocking revulsion at the potential corporeality of desire gives Afrika’s work much of its power.

Bonds between men

… the question of male bonding… is one on which I hold particularly decided views. … I do not think that male bonding is the rugged, virginal affection between males that many books and the cinema screens would have us believe. In fact, the relationship is as lushly suggestive of intercourse… as a serious whore’s bed and is… a barely covert celebration of masculinity and a sharing, as barely restrained, of a hunger to once again run in packs and, together, rape and rend. Or did you really think that gay rape was a phenomenon of this day and age alone? And an adolescent, swinging between his Yin and his Yang … would such a bonding benefit or harm him?From Mr Chameleon, 2005

From early adulthood Afrika moved in male-dominated environments. In the 1940s he was a young soldier and prisoner of war and in the 1980s a political prisoner. He worked in small, outlying farming and mining towns with predominantly male companionship. Male hierarchies were also foremost in the public, active life he chose as a Muslim and anti-apartheid activist from the mid-1960s onwards.

In his life, and much of his writing, Afrika is intensely focused on matters of sexual identity and belonging. His intimate emotional connections are with men and the author moves between homoerotic and homophobic preoccupations. This conflict is never resolved. Even in Bitter Eden, where he fictionalises the dilemma of same-sex attraction, he cannot find middle-ground between an acceptable desire and taboo behaviour.

Although Afrika recoils from overt male desire, he demonstrates a fascination with the gay community in Cape Town. In the poem ‘Gay Samaritans’ he portrays a flamboyant couple who befriended him. In his work there is a sense of strong identification with the warmth he sees in meetings between men and a sense of wonder at men who feel easy in their nakedness.

The poem ‘The Groping’ presents a scene of sexual harassment, but it is also an example of his tendency to describe what is unwanted and ugly as feminine. Afrika’s conflicted nature also comes to the fore in the poems ‘Grey Man’ and ‘The Seeding’ where there is a movement between revulsion and tenderness, while ‘War Mate’ presents male bonding in heroic terms.

Afrika is willing to reveal his conflicted being. The tension between a desire to bond with other males and an often shocking revulsion at the potential corporeality of desire gives Afrika’s work much of its power.

A home in Islam

… and I am leaping outinto the minaret-steep

of abstinence, tail

swinging like the ape’s I am

and the white

impertinence of my piety already rent

as my unaccustomed angel’s wings

flop me before my Lord

From ‘Readying for Ramadaan’, 1995

Afrika’s move to Cape Town in the 1960s, together with having himself reclassified as Malay (non-white) and converting to Islam, proved a turning point in his life. He searched for an African identity through Islam, empathy with other black people, activism and writing anti-apartheid tracts. He fell foul of the South African government when Al-Jihaad, the organisation to which he belonged, protested against the forced removals of District Six and lent its support to the Arabs in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War.

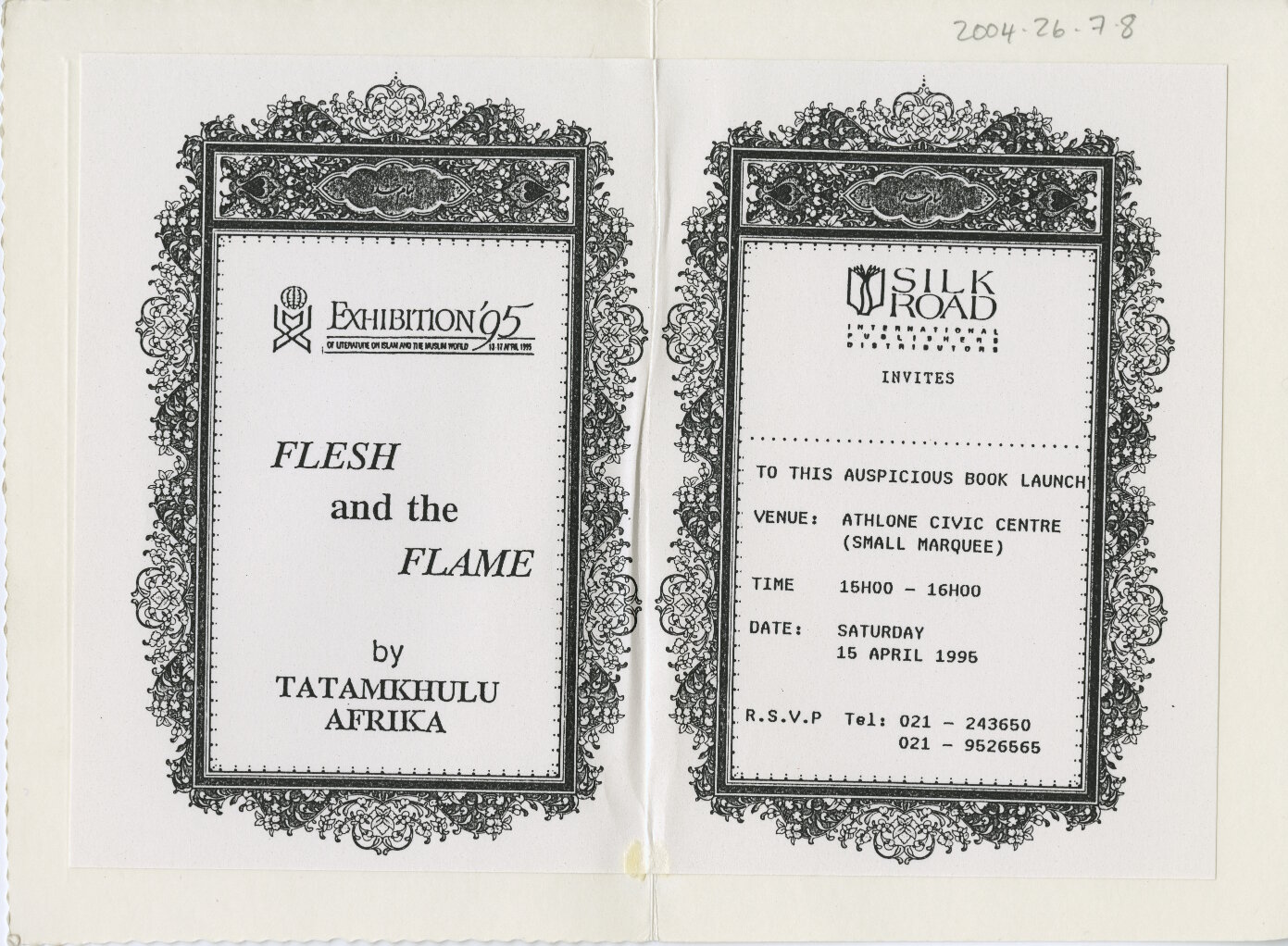

A return to his Muslim roots represented the end of Afrika’s chameleon identity. He had found his true colours. Flesh and the Flame is a collection of poetry focused on spirituality, particularly Islamic religious life. Poems from other collections that refer to his conversion are ‘Boeta’ and ‘The Teacher’.

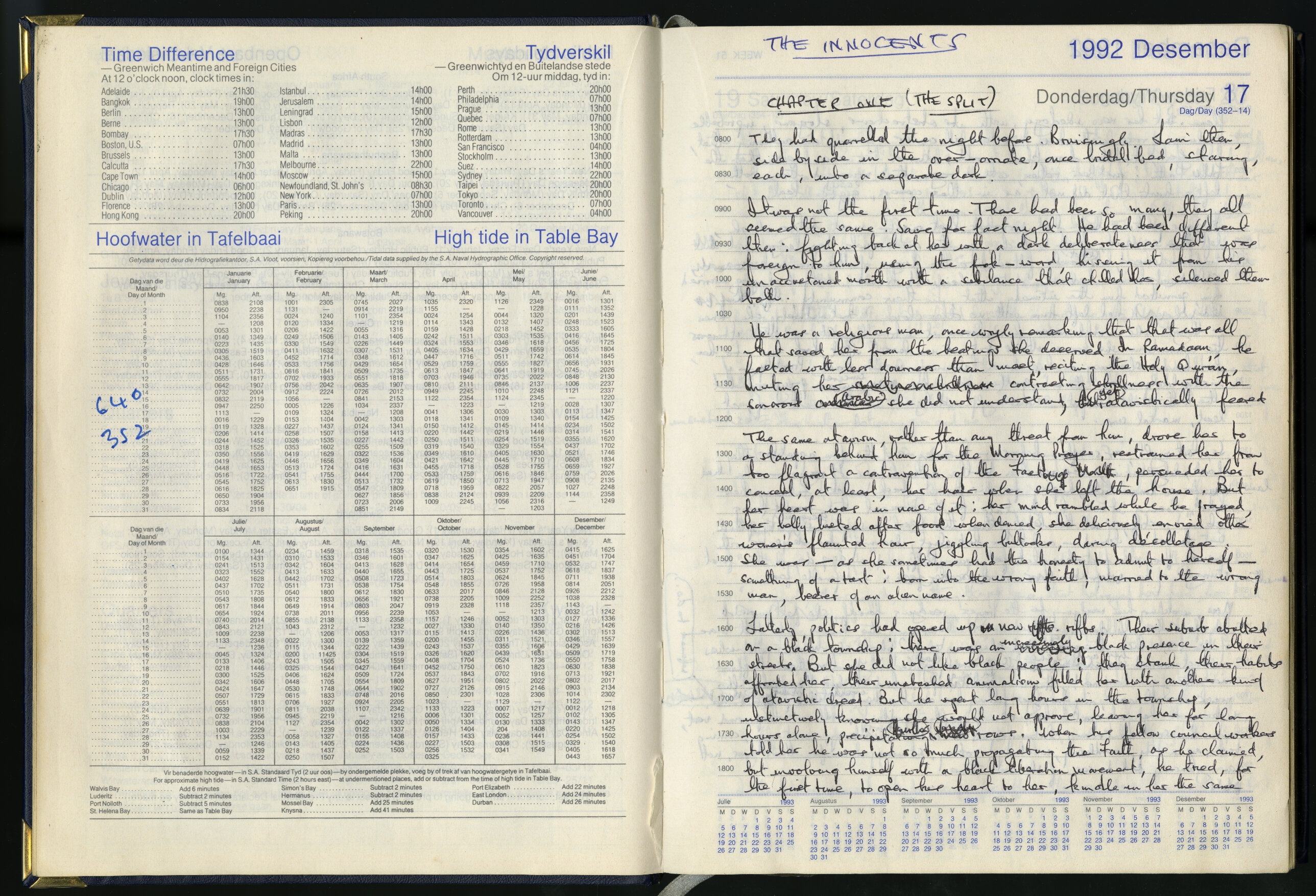

The 1994 novel The Innocents is largely based on Afrika’s experience as a Muslim activist. The main character Yusuf leads a small band of Muslim men who commit acts of terrorism in Cape Town, mainly by planting home-made bombs. Questions such as the Muslim injunction against taking life and racial prejudice between black and coloured people are brought to the fore. The Innocents is an important work of South Africa’s struggle literature as it represents protest, arrest, torture, trial and prison experiences of this era.

A home in Islam

… and I am leaping outinto the minaret-steep

of abstinence, tail

swinging like the ape’s I am

and the white

impertinence of my piety already rent

as my unaccustomed angel’s wings

flop me before my Lord

From ‘Readying for Ramadaan’, 1995

Afrika’s move to Cape Town in the 1960s, together with having himself reclassified as Malay (non-white) and converting to Islam, proved a turning point in his life. He searched for an African identity through Islam, empathy with other black people, activism and writing anti-apartheid tracts. He fell foul of the South African government when Al-Jihaad, the organisation to which he belonged, protested against the forced removals of District Six and lent its support to the Arabs in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War.

A return to his Muslim roots represented the end of Afrika’s chameleon identity. He had found his true colours. Flesh and the Flame is a collection of poetry focused on spirituality, particularly Islamic religious life. Poems from other collections that refer to his conversion are ‘Boeta’ and ‘The Teacher’.

The 1994 novel The Innocents is largely based on Afrika’s experience as a Muslim activist. The main character Yusuf leads a small band of Muslim men who commit acts of terrorism in Cape Town, mainly by planting home-made bombs. Questions such as the Muslim injunction against taking life and racial prejudice between black and coloured people are brought to the fore. The Innocents is an important work of South Africa’s struggle literature as it represents protest, arrest, torture, trial and prison experiences of this era.

Political activism

Coming out of prison you were flowing out into an entire nation of oppressed people, which leads to a much wider and sharper reaction, a much greater absorption into people’s suffering and emotions. If I’d never gone to prison … I would not have written anything.From an interview with Robert Berold, 1992.

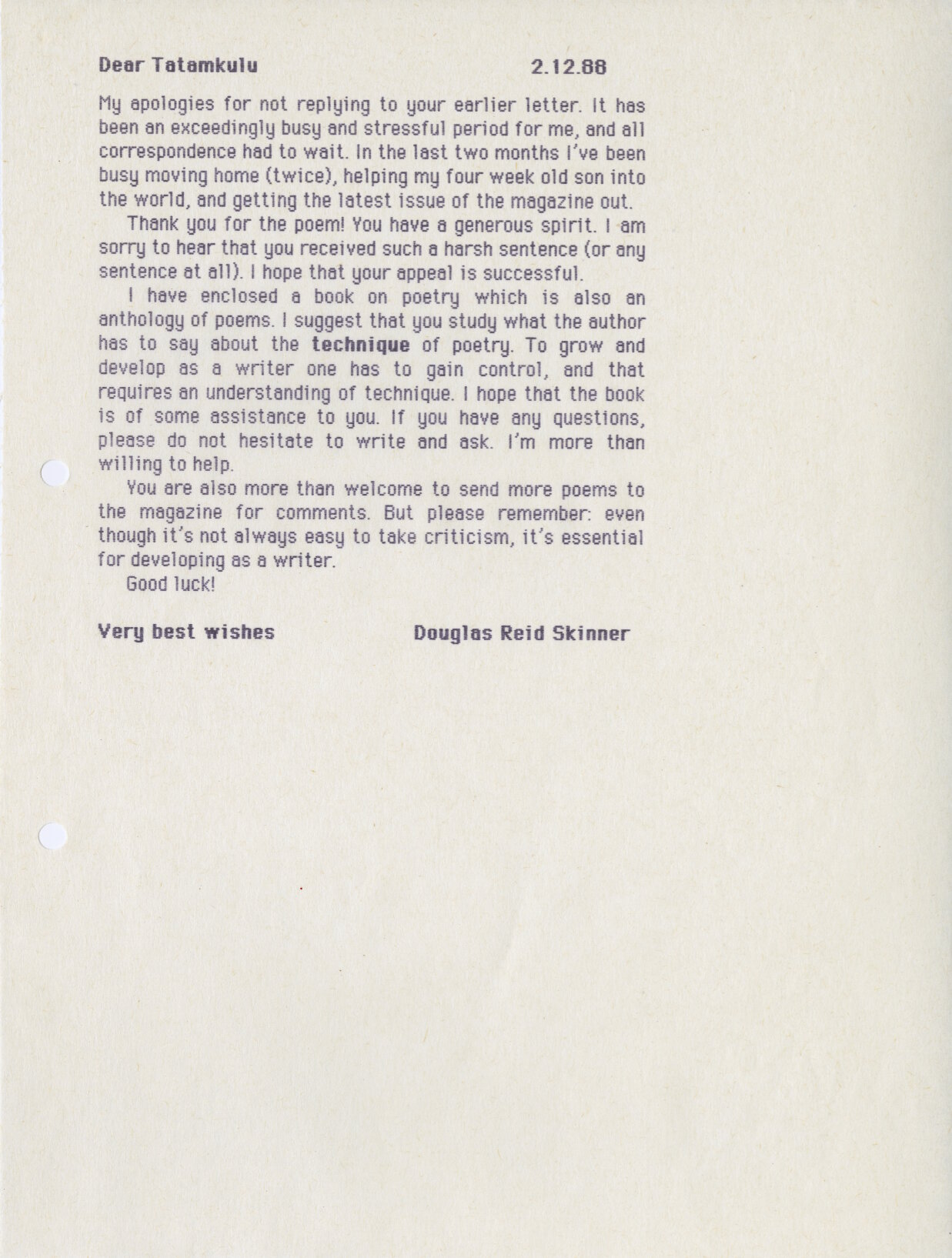

Afrika put together a pamphlet ‘Poems of Penance and Protest’ under the name Ismail Joubert and, together with other members of Al-Jihaad, joined uMkhonto weSiswe, the armed wing of the African National Congress, in the 1980s. He was arrested for terrorism in May 1987 and spent time in and out of prison on bail for the next two years between the arrest, the initial sentence and the appeal to the Supreme Court, where his four-year prison sentence was suspended. This is when his comrades bestowed the name Tatamkhulu Afrika on him. Enraged by the way the hopes and lives of ordinary people were wrecked by the oppressive system of apartheid, he started to write under this name, even though he was banned and forbidden to write for five years.

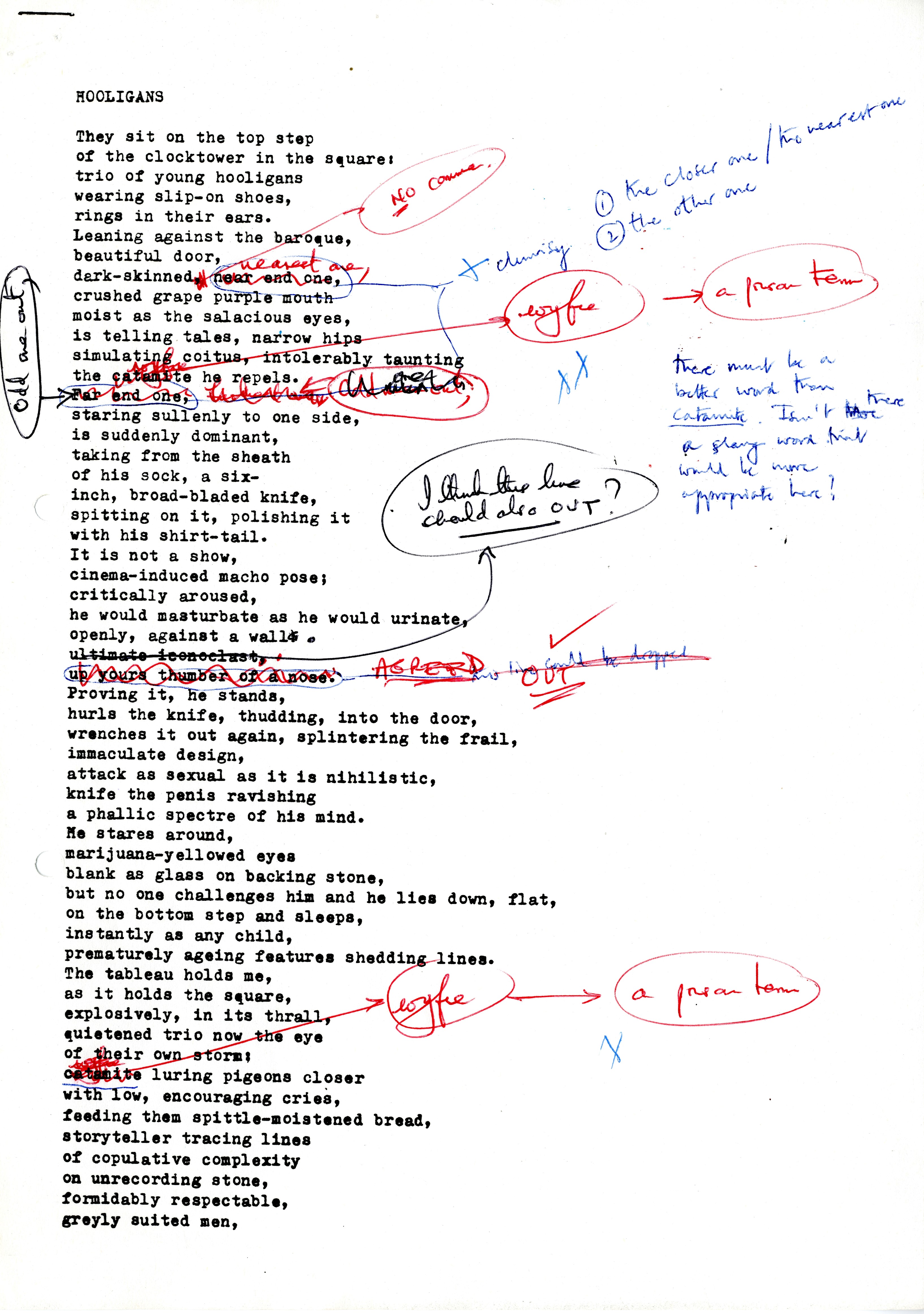

Afrika was concerned with the inaccessibility of modernist poetry and the need for a “people’s poetry”. Although he wrote about protest marches, the funerals of struggle heroes and meetings with political leaders, many of his poems express disillusionment with the post-freedom reality in which destitute and ordinary people were forgotten. The collections of the 1990s – Nine Lives, Dark Rider, Maqabane and Turning Points – contain Afrika’s most political poetry.

Political activism

Coming out of prison you were flowing out into an entire nation of oppressed people, which leads to a much wider and sharper reaction, a much greater absorption into people’s suffering and emotions. If I’d never gone to prison … I would not have written anything.From an interview with Robert Berold, 1992.

Afrika put together a pamphlet ‘Poems of Penance and Protest’ under the name Ismail Joubert and, together with other members of Al-Jihaad, joined uMkhonto weSiswe, the armed wing of the African National Congress, in the 1980s. He was arrested for terrorism in May 1987 and spent time in and out of prison on bail for the next two years between the arrest, the initial sentence and the appeal to the Supreme Court, where his four-year prison sentence was suspended. This is when his comrades bestowed the name Tatamkhulu Afrika on him. Enraged by the way the hopes and lives of ordinary people were wrecked by the oppressive system of apartheid, he started to write under this name, even though he was banned and forbidden to write for five years.

Afrika was concerned with the inaccessibility of modernist poetry and the need for a “people’s poetry”. Although he wrote about protest marches, the funerals of struggle heroes and meetings with political leaders, many of his poems express disillusionment with the post-freedom reality in which destitute and ordinary people were forgotten. The collections of the 1990s – Nine Lives, Dark Rider, Maqabane and Turning Points – contain Afrika’s most political poetry.

Portraits of people

His face contorted and the slack throat stretched,and, with a power of his lost youth, he yelled

out the old call to freedom we had known so well.

But his hand sought my shoulder when he stood

…

and he shuffled off along the cold, dry riverbed,

with its broken glass and empty, rusting cans,

every day as old as his eighty-seven years.

From ‘The Veteran’, 1991

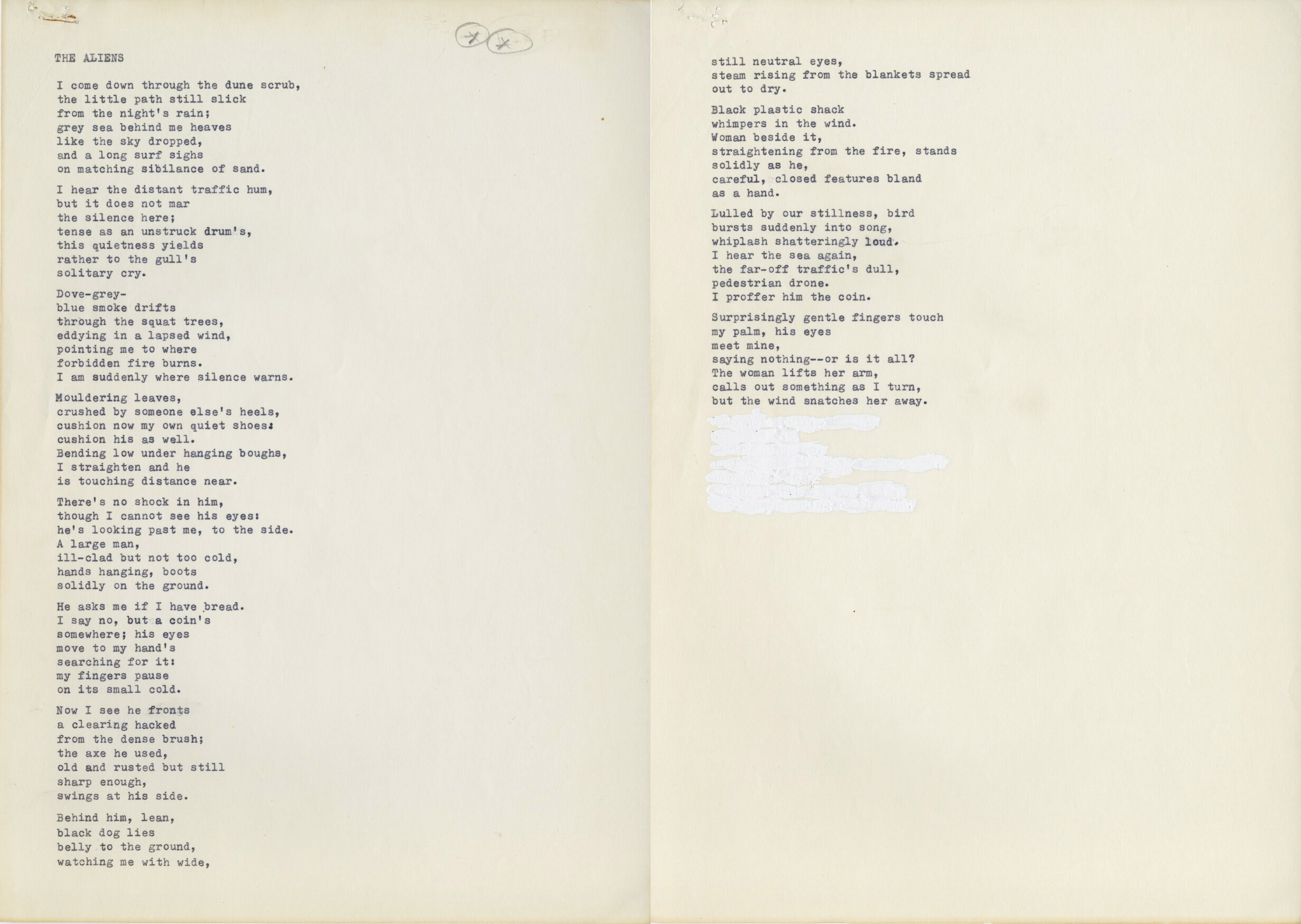

Afrika is known for the remarkable way in which he created portraits of people in his poetry that read like the start of stories. He wrote about people on the margins of society, struggle victims, street people, the dispossessed, minor gangsters, as well as old flames, clerks and people in queues. These portraits are striking because of his interest in these people, his observations and his openness to the interior life of another being.

Afrika remarked that if you see yourself as “all people”, you have no armour between yourself and others. This compassion, together with the honesty in which he presents his inner conflicts, especially in terms of relating intimately to people, gives the reader a portrait of Tatamkhulu Afrika not only as an individual, but also as someone engaged with social justice in the world.

Portraits of people

His face contorted and the slack throat stretched,and, with a power of his lost youth, he yelled

out the old call to freedom we had known so well.

But his hand sought my shoulder when he stood

…

and he shuffled off along the cold, dry riverbed,

with its broken glass and empty, rusting cans,

every day as old as his eighty-seven years.

From ‘The Veteran’, 1991

Afrika is known for the remarkable way in which he created portraits of people in his poetry that read like the start of stories. He wrote about people on the margins of society, struggle victims, street people, the dispossessed, minor gangsters, as well as old flames, clerks and people in queues. These portraits are striking because of his interest in these people, his observations and his openness to the interior life of another being.

Afrika remarked that if you see yourself as “all people”, you have no armour between yourself and others. This compassion, together with the honesty in which he presents his inner conflicts, especially in terms of relating intimately to people, gives the reader a portrait of Tatamkhulu Afrika not only as an individual, but also as someone engaged with social justice in the world.

Old Man day-by-day

And I am my own self’sshutting down,

hiccupping blood’s crawl,

step by shortening step

faltering into stone

From ‘Slow-motion man’, 2000.

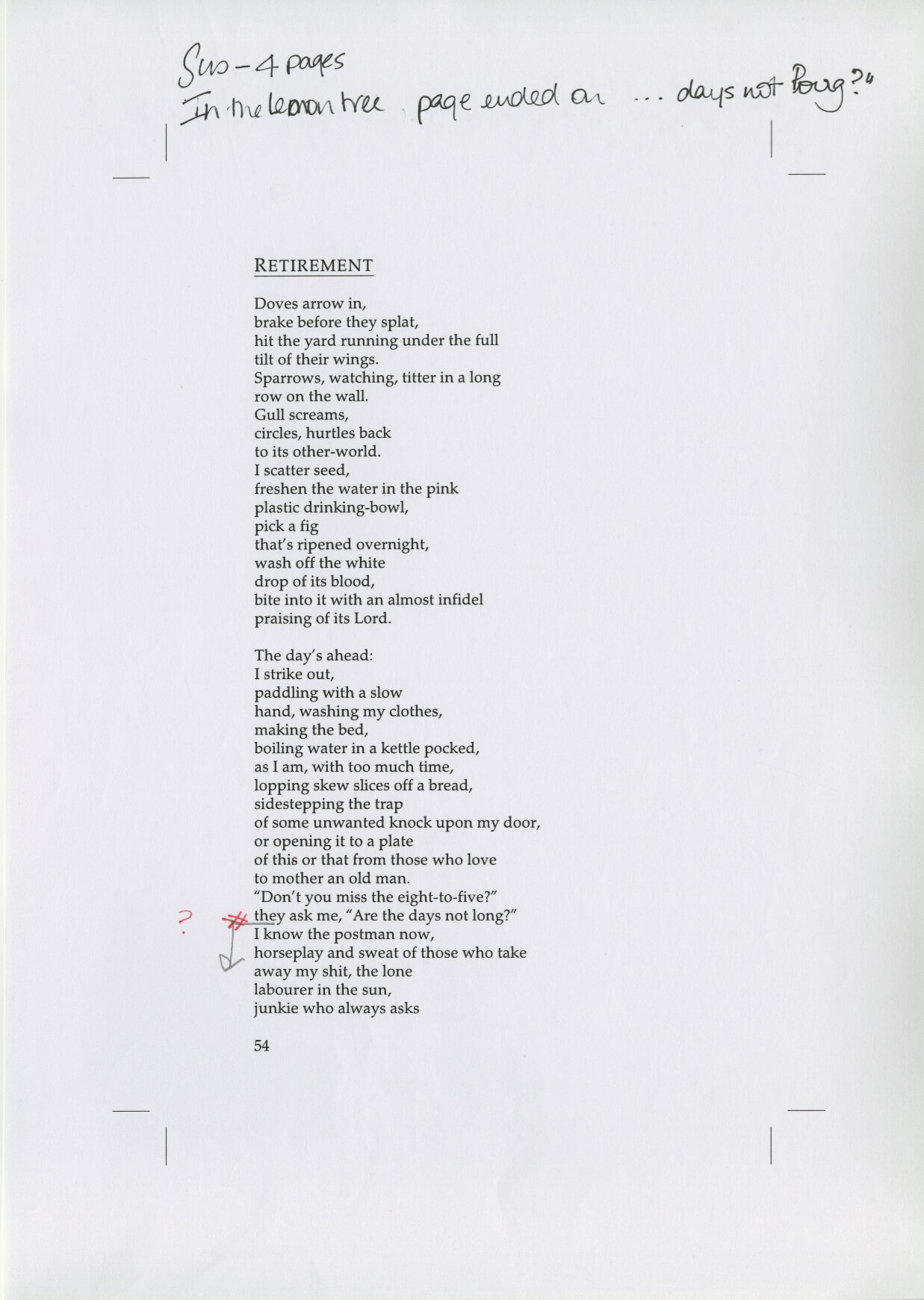

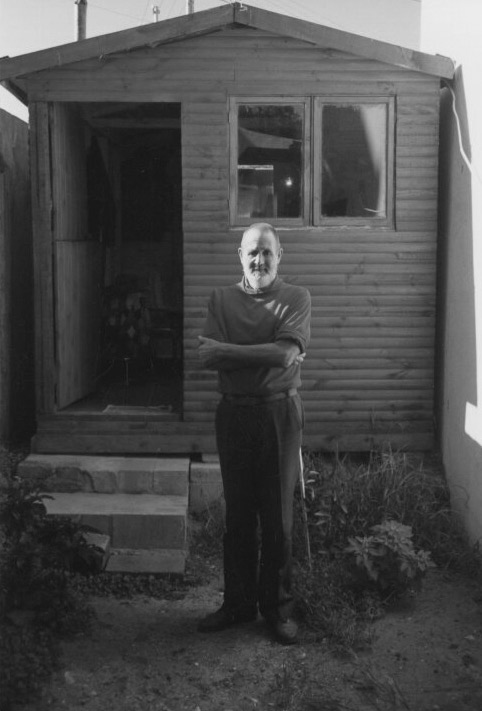

Upon arriving in Cape Town in the early 1960s, Afrika soon found himself close to destitution. He scraped together meals by pilfering from fruit lorries and events until he eventually found a job at an accounting firm. The poem ‘Waiting for Mr January’ presents the speaker at the mercy of officialdom for a social grant application, an experience Afrika also mentions in his autobiography. His housing situation was precarious and it was only after he won the Sanlam Literary Award for Mad Old Man Under the Morning Star in 2000 that he could gain some independence by buying a wendy house, which he erected in a backyard in the Bo-Kaap.

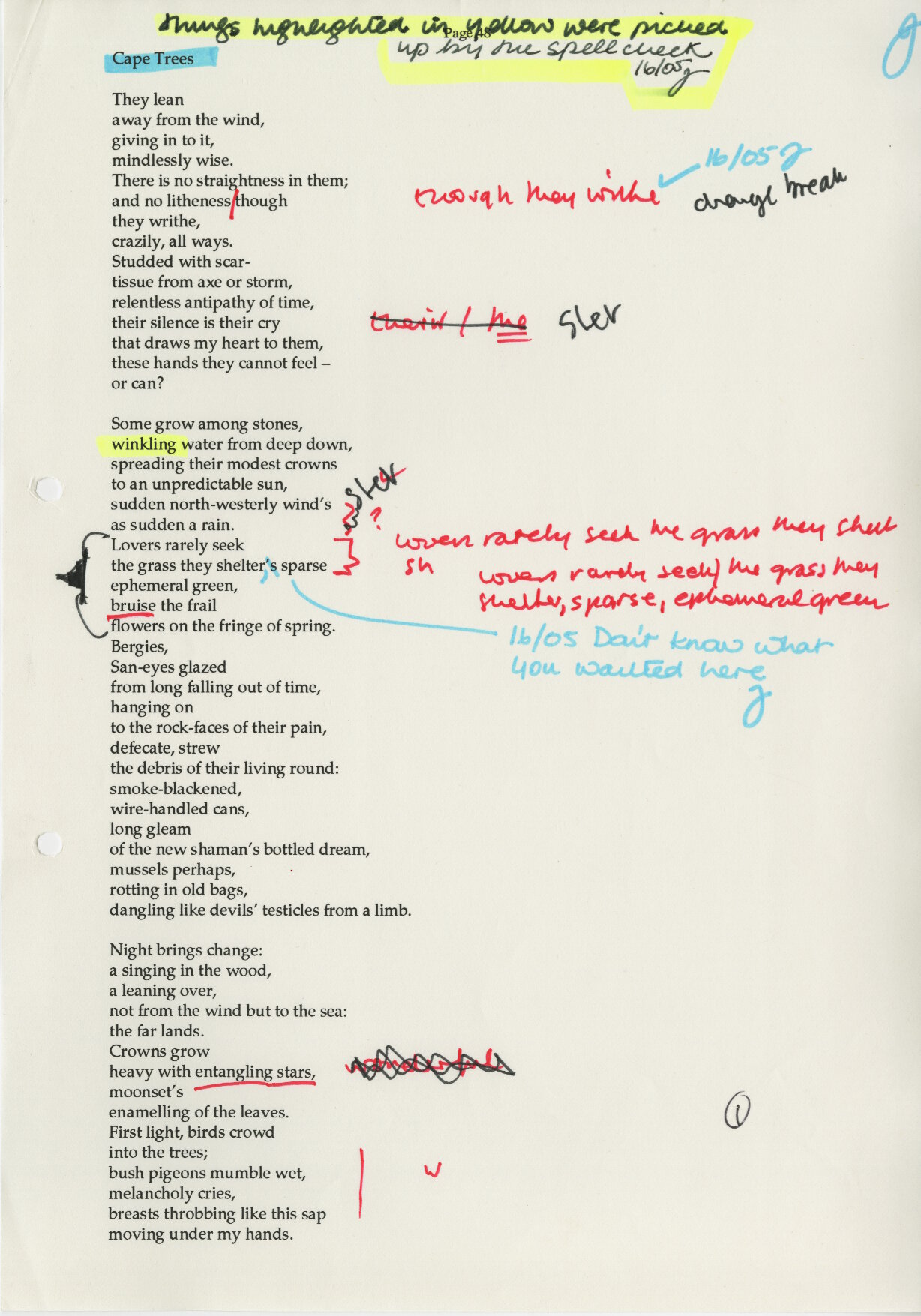

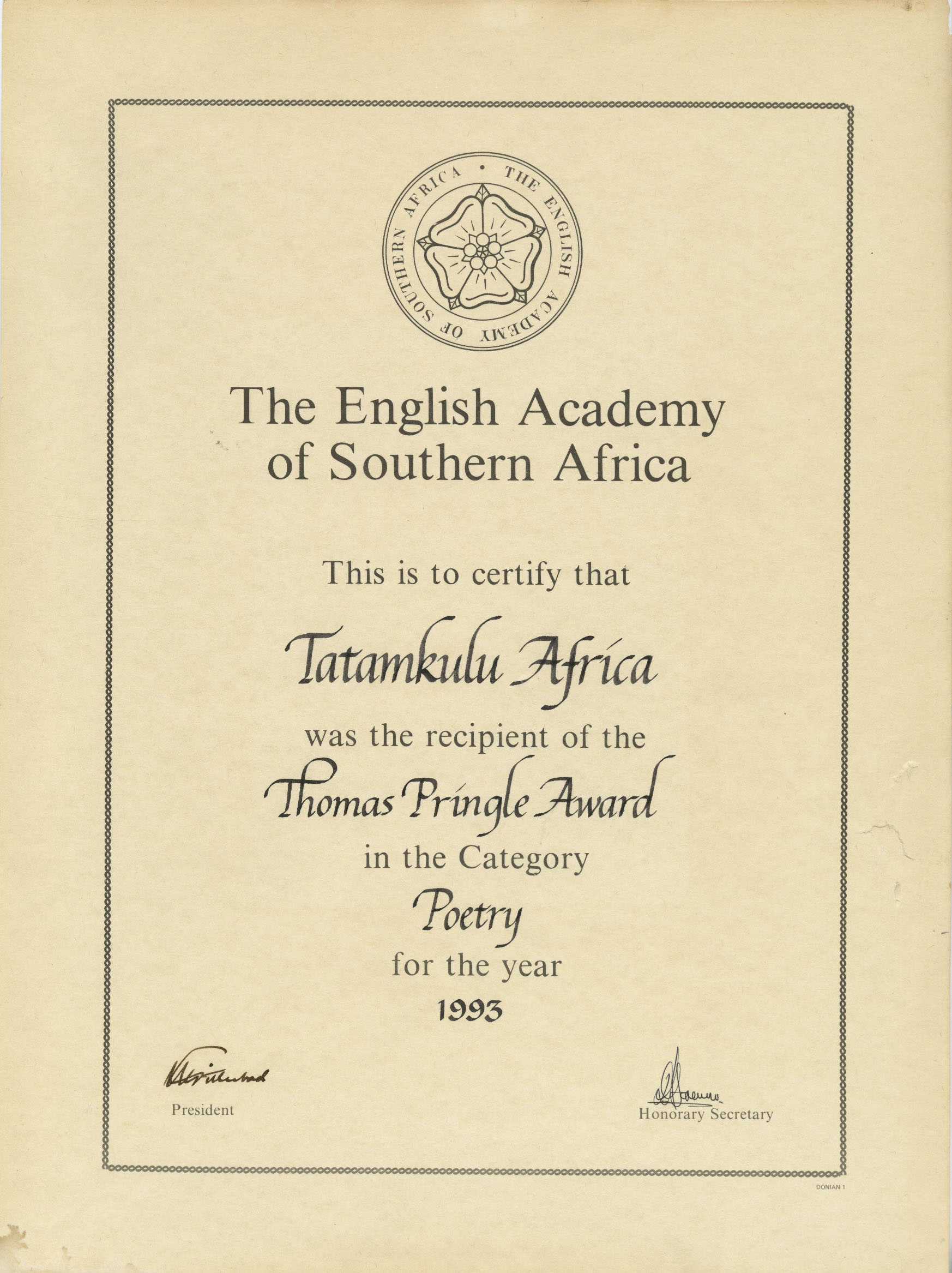

Many of Afrika’s poems are about his everyday life in Cape Town: the lemon tree in his garden, feeding birds, dawn breaking over the ocean, cycling through the city’s streets. He also expresses fear of the violence of urban life. Afrika was attacked several times and the poem ‘The Mugging’, which is based on such an incident, won the 1993 Thomas Pringle Award. He describes the loneliness and fears of growing old, his body – and in particular his eyesight – failing.

Poetry collections with a stronger leaning towards these themes are: The Lemon Tree (1995), The Angel and Other Poems (1999),and Mad Old Man under the Morning Star (2000).

Old Man day-by-day

And I am my own self’sshutting down,

hiccupping blood’s crawl,

step by shortening step

faltering into stone

From ‘Slow-motion man’, 2000.

Upon arriving in Cape Town in the early 1960s, Afrika soon found himself close to destitution. He scraped together meals by pilfering from fruit lorries and events until he eventually found a job at an accounting firm. The poem ‘Waiting for Mr January’ presents the speaker at the mercy of officialdom for a social grant application, an experience Afrika also mentions in his autobiography. His housing situation was precarious and it was only after he won the Sanlam Literary Award for Mad Old Man Under the Morning Star in 2000 that he could gain some independence by buying a wendy house, which he erected in a backyard in the Bo-Kaap.

Many of Afrika’s poems are about his everyday life in Cape Town: the lemon tree in his garden, feeding birds, dawn breaking over the ocean, cycling through the city’s streets. He also expresses fear of the violence of urban life. Afrika was attacked several times and the poem ‘The Mugging’, which is based on such an incident, won the 1993 Thomas Pringle Award. He describes the loneliness and fears of growing old, his body – and in particular his eyesight – failing.

Poetry collections with a stronger leaning towards these themes are: The Lemon Tree (1995), The Angel and Other Poems (1999),and Mad Old Man under the Morning Star (2000).

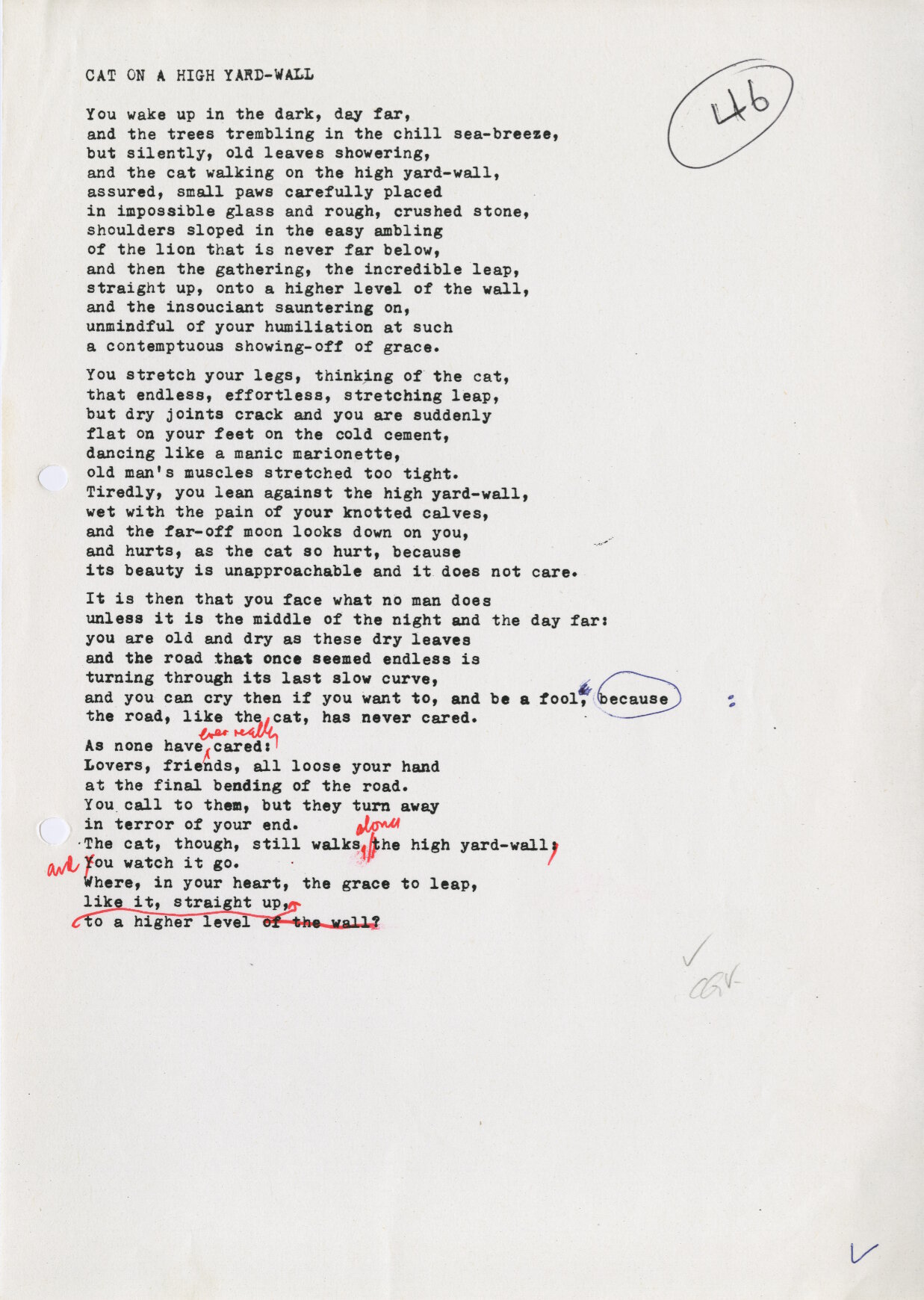

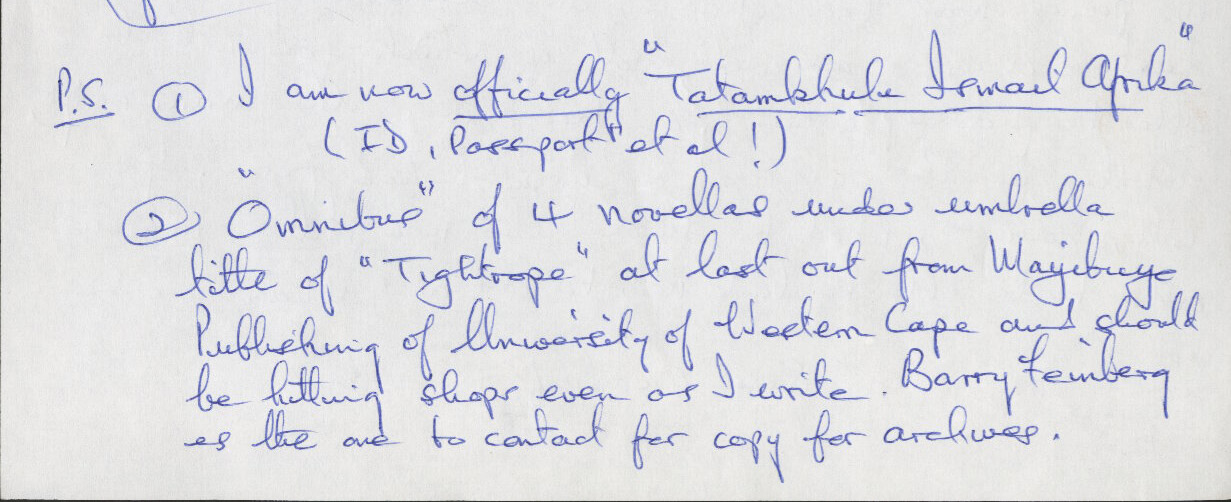

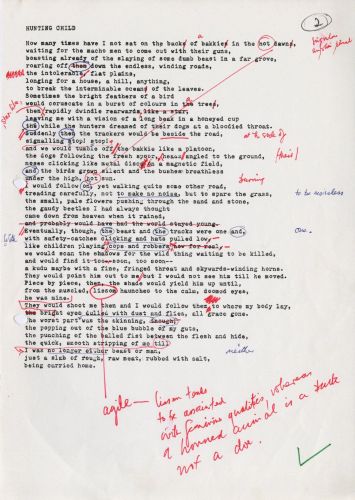

Writing into the world

I have no conscious style – I just write down what comes to me in the way it comes to me and that’s that! I do, of course, subsequently spend a lot of time polishing rhythm and weeding out clichés… I hear cadences rather than “arrange” anything in “paragraphs”, I try to set out the lines in such a way that the reader hear the cadences in the same way that I do.From a letter to Marge Clouts, 3 May 1993.

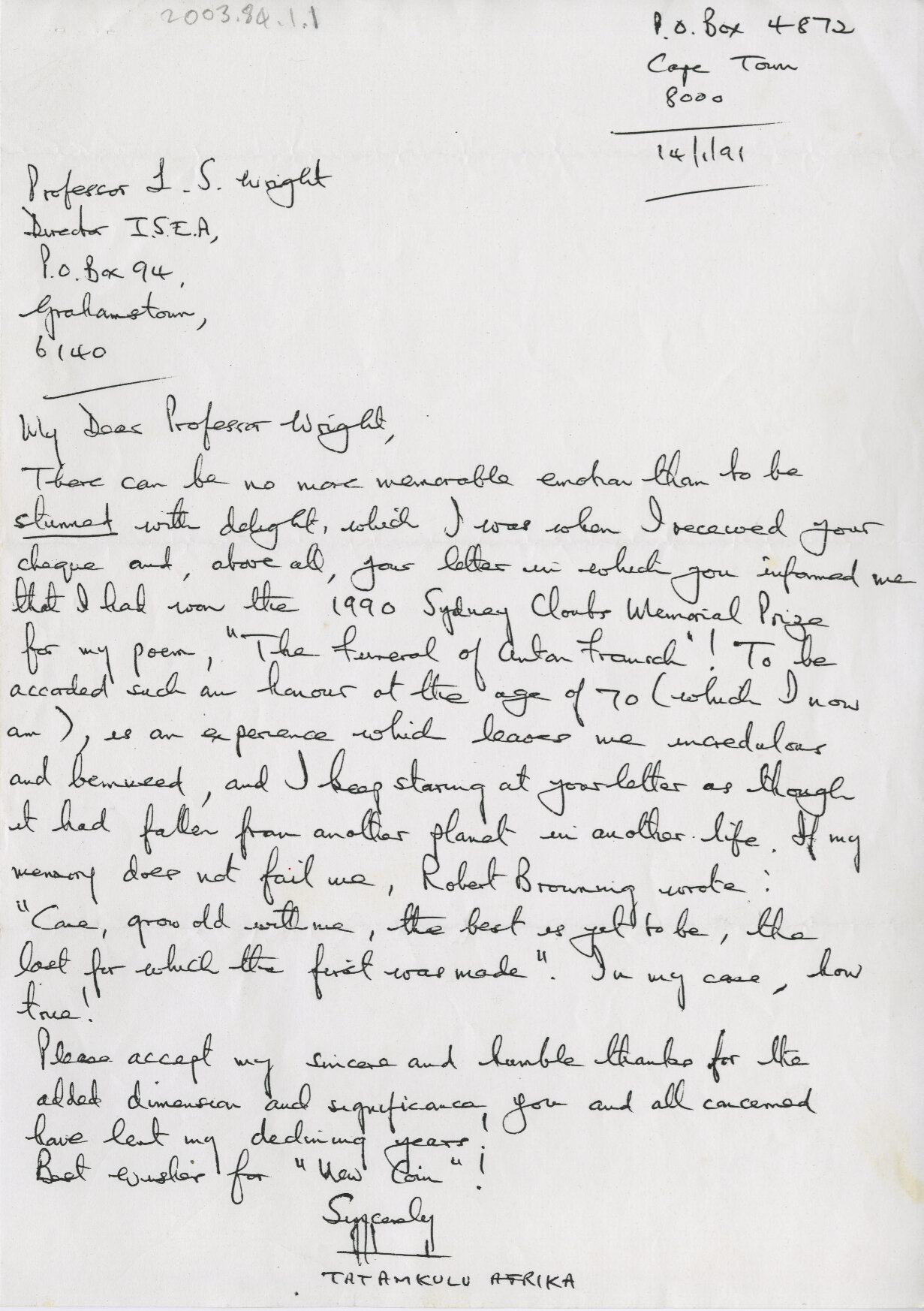

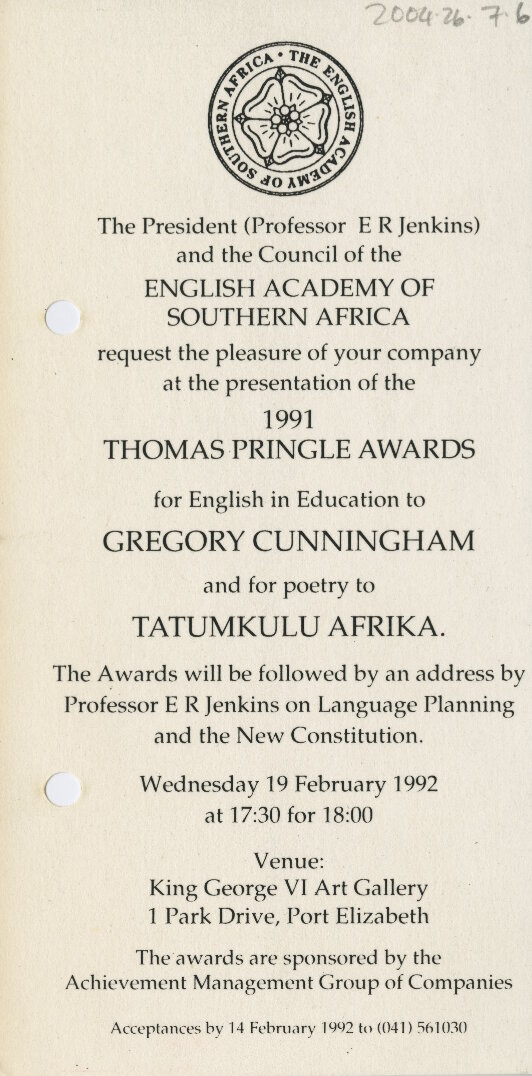

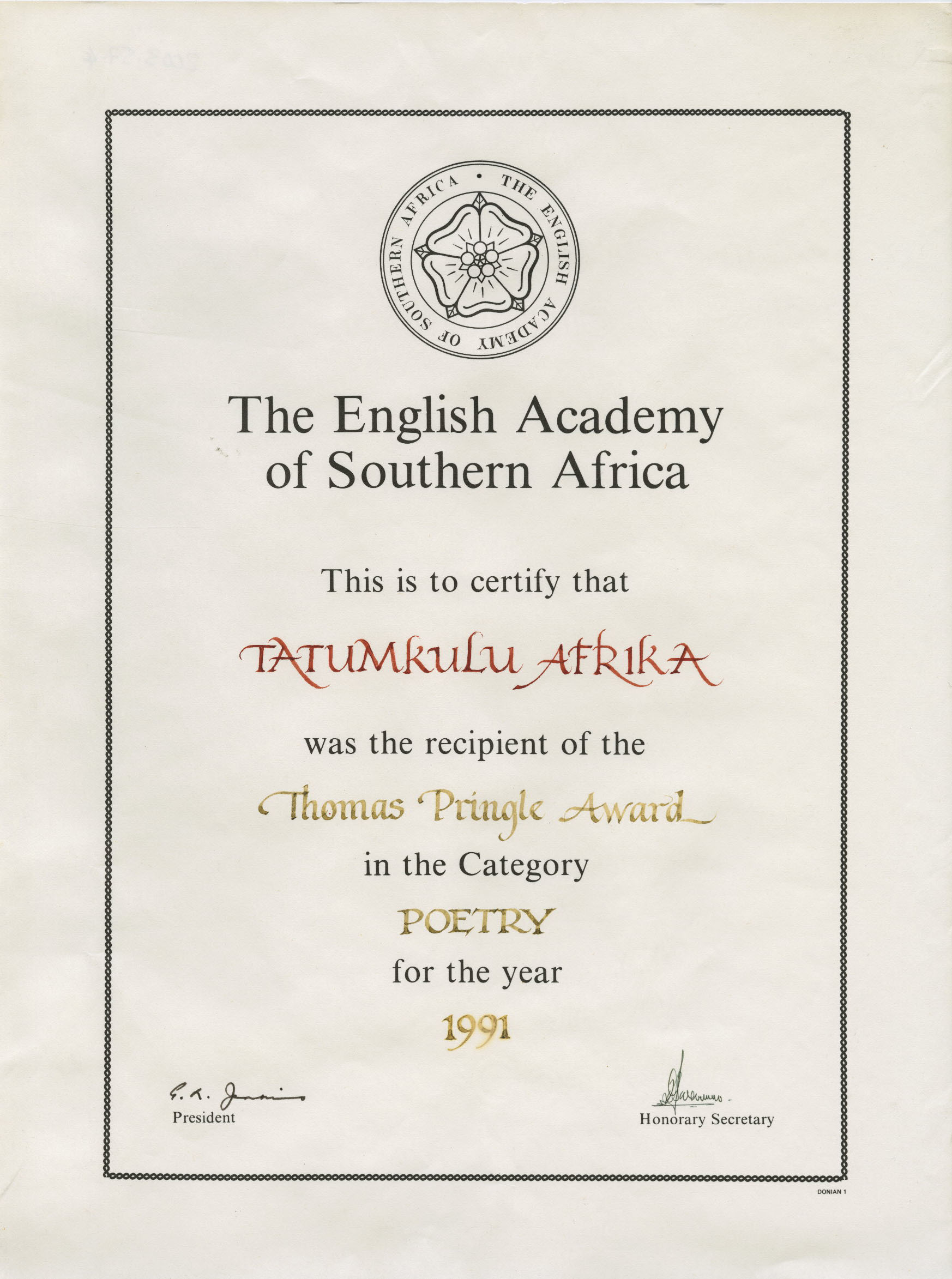

Afrika’s literary achievements have been recognised by the South African literary establishment. The war novel Bitter Eden has been translated into several languages and The Innocents, first published in South Africa in 1994, was published internationally in 2006. He won many of South Africa’s important literary awards.

A volume of selected works, Nightrider, was published posthumously in 2003, bringing together poems from his collections, journals and some previously unpublished works.

Nelson Mandela, President of the ANC at the time, sent a formal letter of congratulations to ‘Dear Cde Tatamkulu’ on the publication of Dark Rider in 1993. Despite his success, Afrika complained about critics and a lack of recognition. Some critics judge his language as too flowery and reason that he overstates what he wants to say in his poems. Many readers find his style conventionally romantic and say that he writes fluently from an ideal of humanism. Still, it was important to Afrika that he communicate clearly about the things he deemed important.

Writing into the world

I have no conscious style – I just write down what comes to me in the way it comes to me and that’s that! I do, of course, subsequently spend a lot of time polishing rhythm and weeding out clichés… I hear cadences rather than “arrange” anything in “paragraphs”, I try to set out the lines in such a way that the reader hear the cadences in the same way that I do.From a letter to Marge Clouts, 3 May 1993.

Afrika’s literary achievements have been recognised by the South African literary establishment. The war novel Bitter Eden has been translated into several languages and The Innocents, first published in South Africa in 1994, was published internationally in 2006. He won many of South Africa’s important literary awards.

A volume of selected works, Nightrider, was published posthumously in 2003, bringing together poems from his collections, journals and some previously unpublished works.

Nelson Mandela, President of the ANC at the time, sent a formal letter of congratulations to ‘Dear Cde Tatamkulu’ on the publication of Dark Rider in 1993. Despite his success, Afrika complained about critics and a lack of recognition. Some critics judge his language as too flowery and reason that he overstates what he wants to say in his poems. Many readers find his style conventionally romantic and say that he writes fluently from an ideal of humanism. Still, it was important to Afrika that he communicate clearly about the things he deemed important.

Dare we make our worlds, our dreams real? Dare we be in the silence of the country and stand on that mountain, shouting at the world?

Making it real

Tatamkhulu Afrika’s work is driven by an urgency of message. His focus on the lives of the marginalised and the dispossessed enables his writing to act as protest against the injustices of apartheid and his later work continues to be an act of protest against the failures of the country’s transition to democracy.

The seriousness of his purpose is already evident in the 17-year old author of Broken Earth, who wished to entertain, but also to make his vision real.

Everyone should be forced by law to write a book.

In the first place it will probably be the most exciting thing that will ever happen to you… .

Secondly the potential author creates so much fun for himself and other people. Especially other people. During the opening chapters of this book I used to insist on the playing of waltz records so as to simulate thought. Nearly everybody could see the funny side of that. I was one of those who could not.

…I quite realise that it may not be even a very interesting book. But I have tried to make it real. I have sat in the very heart of the country I have chosen to write about and I have described exactly as I have seen it. The characters may seem over-neurotic, perhaps over-poetic, but sit alone in a room in the country as I have done and you will realize that the silence of the country can do strange things to one.

From the preface to Broken Earth, 1940/1.

Making it real

Tatamkhulu Afrika’s work is driven by an urgency of message. His focus on the lives of the marginalised and the dispossessed enables his writing to act as protest against the injustices of apartheid and his later work continues to be an act of protest against the failures of the country’s transition to democracy.

The seriousness of his purpose is already evident in the 17-year old author of Broken Earth, who wished to entertain, but also to make his vision real.

Everyone should be forced by law to write a book.

In the first place it will probably be the most exciting thing that will ever happen to you… .

Secondly the potential author creates so much fun for himself and other people. Especially other people. During the opening chapters of this book I used to insist on the playing of waltz records so as to simulate thought. Nearly everybody could see the funny side of that. I was one of those who could not.

…I quite realise that it may not be even a very interesting book. But I have tried to make it real. I have sat in the very heart of the country I have chosen to write about and I have described exactly as I have seen it. The characters may seem over-neurotic, perhaps over-poetic, but sit alone in a room in the country as I have done and you will realize that the silence of the country can do strange things to one.

From the preface to Broken Earth, 1940/1.

A selection of works by Tatamkhulu Afrika

Poetry

The Angel and Other Poems.1999).

Dark Rider. 1992.

Flesh and the Flame. 1995.

The Lemon Tree: Poems. 1995.

Mad Old Man under the Morning Star: The Poet at Eighty. 2001.

Maqabane. 1994.

Nightrider: Selected Poems. 2003.

Nine Lives. 1991.

Turning Points. 1996.

Fiction

Bitter Eden. 2002.

Broken Earth. 1940/41. [As John Charlton]

The Innocents. 1994.

Tightrope : Four Novellas. 1996.

- The Vortex

- The Treadmill

- The Quarry

- The Trap

Articles

'Against all odds, my heart sings.’ Published in Tribute Jul. 1994.

'Bleak look back.' Published in 27 April : One Year Later = Een Jaar Later (compiled by André P. Brink). 1995.

'Miles to go before we sleep: Is political poetry dead after February 1990? Published in

Ditaba * Izindaba (4), 1992.

Interview

'Tatamkhulu Afrika: June 1992.' Published in South African Poets on Poetry: Interviews from New Coin 1992-2001 (edited by Robert Berold, Robert). 2003.

Short stories written as John Charlton

‘The Second Lantern.’ Published in The Nongqai, Jul. 1946.

‘Leopard Man.’ Published in The Nongqai, Jun. 1946.

'The Devil's Children.' Published in The Nongqai, May 1946.

Journals

These are among the journals Afrika published his work in: Al-Fil-ul-Islam; Botsotso; Carapace; The English Academy Review; New Coin; New Contrast; Sesame; Slug Newsletter; Spectrum; Staffrider; Tribute; Upstream.A selection of works by Tatamkhulu Afrika

Poetry

The Angel and Other Poems.1999).

Dark Rider. 1992.

Flesh and the Flame. 1995.

The Lemon Tree: Poems. 1995.

Mad Old Man under the Morning Star: The Poet at Eighty. 2001.

Maqabane. 1994.

Nightrider: Selected Poems. 2003.

Nine Lives. 1991.

Turning Points. 1996.

Fiction

Bitter Eden. 2002.

Broken Earth. 1940/41. [As John Charlton]

The Innocents. 1994.

Tightrope : Four Novellas. 1996.

- The Vortex

- The Treadmill

- The Quarry

- The Trap

Articles

'Against all odds, my heart sings.’ Published in Tribute Jul. 1994.

'Bleak look back.' Published in 27 April : One Year Later = Een Jaar Later (compiled by André P. Brink). 1995.

'Miles to go before we sleep: Is political poetry dead after February 1990? Published in

Ditaba * Izindaba (4), 1992.

Interview

'Tatamkhulu Afrika: June 1992.' Published in South African Poets on Poetry: Interviews from New Coin 1992-2001 (edited by Robert Berold, Robert). 2003.

Short stories written as John Charlton

‘The Second Lantern.’ Published in The Nongqai, Jul. 1946.

‘Leopard Man.’ Published in The Nongqai, Jun. 1946.

'The Devil's Children.' Published in The Nongqai, May 1946.

Journals

These are among the journals Afrika published his work in: Al-Fil-ul-Islam; Botsotso; Carapace; The English Academy Review; New Coin; New Contrast; Sesame; Slug Newsletter; Spectrum; Staffrider; Tribute; Upstream.